Februrary is ‘Rare Disease’ month. Please read more about the importance of raising awareness, improving care and support in rare diseases (including further references) in my post from last year. Examples for rare conditions are severe motility disorder such as chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction (CIPO). More information can be found here including the information pack. Some art projetcs ‘Selten allein’ can be seen online and in person.

I hope to update soon. Unfortunately, my health has further declined (slowly, but steady). Emergency situations are treated, symptoms are dealt with, the illness(es) is (are) beyond treatable/manageable/bearable … I am under palliative care (more about this in the following post), but they simply cannot do much. Daily nausea with and without vomiting as well as extreme pain have further increased. Instead of weight stabilisation my weight is slowly dropping. We are very exhausted and desperate for some kind of stabilisation, some kind of change, some miracle to happen. I definitely cannot go on like that. Fortunately, I will be admitted at the transplant clinic this week, both for weight stabilisation/gain (we need to find the cause for weight loss despite adaptations of compounding TPN and increase in calories) and transplant evaluation. Fingers crossed.

John Keat’s ‘To Hope‘ reminds us to not give up, the power of hope is immense. When we feel lost, words can lift us up.

Therapy Part II

Following the last post I continue my thoughts on caregiving.

Interview with a caregiver mum

follows soon…

Palliative Care

In severe progressive illness or terminate illness, doctors will talk with you about palliative care. End-of-life care may mean the transfer to another care facility or a hospice programme.

Palliative care is medical caregiving for patients that have a serious, often complex and/or terminal illness with the aim of increasing quality of life, thus, decreasing suffering i.e. symptoms as needed. However, palliative care is not equivalent to end-of-life care which is again not equivalent to no therapy option left anymore. Palliative care may be given along with other curative therapies (i.e. therapies that may improve health) whereas during end-of-life treatment all curative therapy options are stopped.

Palliative care in severe illness includes the alleviation of symptoms, family support, alignment of treatment with the patient’s preferences and values i.e. the patient and the medical team work hand in hand and the treatment is based on patients needs, not on his/her prognosis. It takes a much more broader patient-centred approach than the usual medical options.

Obviously, the medical therapies depend on the underlying condition, but often it is the alleviation of pain, nausea, psychological issues such as depression or anxiety, shortness of breath, fatigue, constipation, loss of appetite, difficulty sleeping,…

The palliative team should communicate with the patient, his/her family and doctors as well as between the patient and doctors. Care can be provided in hospitals, outpatient palliative care clinics or nursing homes or at home.

Palliative medicine often involves broader pain management tools and palliative care includes educational, spiritual and psychological support for the patient and the family.

My first encounter with palliative care was for pain management. Palliative care doctors and nurses often have a broader knowledge regarding possible pain management options and can provide a more individualised and multidisciplinary space for their trial and implementation. On palliative care wards there are more nurses and doctors per patient, more time for each patient, more individual treatment and treatment that covers the patient as a whole.

Then, when my illness progressed, doctors stated that I have a severe illness that cannot be treated and symptoms are hard(ly) to control, palliative care should support us. We are still waiting for what this exactly means. Obviously, I have a morphine pump (which by no way takes the pain away).

During my stays on the palliative care ward I had wonderful single rooms (where my mum could stay with me), there was a very high nurse- and doctor – to – patient ratio, nurses were able to spend lots of time for support, pain management was following the principle ‘as little pain as possible’, my mum could visit me at any time, …any wish patients have (food, smell, etc) are tried to be met.

In other illnesses such as cancer the oncologist might plan curative treatment (e.g. chemotherapy) whereas the palliative team treats the patient’s symptoms such as nausea, pain or fatigue. In general, they manage care coordination.

In complex, often rare illnesses the patient and family are faced with additional problems such as the lack of support and understanding. Complex conditions often come along with complex pain conditions and/or a complex accumulation of symptoms and treatments beyond standard pain management treatment might be necessary. Psychologists that have a background knowledge in chronic pain/illness and their effect on the life of the patient and family can support, too (for example, psycho oncologists in cancer and psychologists with a special education in pain management).

What we can learn from palliative care is its approach where the patient is at the centre and his/her preferences are included in the treatment plans rather than focusing on the illness only. Moreover, interdisciplinarity is key in symptom management.

Obviously, palliative care is more expensive than standard therapy (and needs sufficient nurses and doctors per patient) and should only be done in severe and/or terminal illness. Nonetheless, it would be good if every medical expert would undergo some kind of palliative care/medicine training. The cultural shift away from disease centred approaches should be taken as an example and topics related to palliative care shouldn’t be such a taboo point in the general public.Unfortunately, patients that suffer from non-malignant chronic diseases usually don’t encounter the advantage of palliative care. Awareness and education programmes as well as better access to palliative care are necessary.

But what if palliative care is left as the only option?

All therapies exhausted. No cure. No or minimal options to improve symptoms and quality of life left anymore.

End-of-Life Treatment

When the patient decides for hospice care he agrees that his/her illness does not respond to any medical attempts. Hence, all curative treatment options are stopped. Hospice care focuses on quality of life, comfort and care of symptoms without the actual necessity of treating the illness or prolonging life.

Moreover, life sustaining treatments can be both wonderful and harsh. Patients already in very poor health don’t necessarily decide to go through each and every treatment out there when they only cause more pain or suffering. Examples are feeding tubes, ventilation, dialysis and more. Pain and short breath are often symptoms that can not be sufficiently reduced. Often therapies can provide life support or sustain life, but do not give any quality of life. As long as the terminally ill patient is conscious and able to make decisions, he/she can decide to stop treatment at any point. In some countries medical aid for dying is also allowed (when the prognosis is six months or less), the patient indigest the medication him/herself. This option makes it possible to die in comfort and at peace. Again, this is different from assisted suicide/euthanasia which can be decided by patients that are not terminally ill, but brings about a peaceful death, too. Often, these are patients that have some incurable disease that causes an extreme amount of pain and/or suffering.* Patients can decide whether to spend their last months in the hospital, at care clinics, in a hospice or nursing homes, on a palliative ward, at some other external institute or at home.

Whereas hospice care is only for terminally ill patients, palliative care is for any seriously ill patient that needs improvement in pain management or other difficult symptoms. Curative treatments are stopped if the patient chooses end-of-life treatment and may be continued or stopped in palliative care. Both provide symptom relief as much as possible. Palliative care may also be included in hospice care during symptom management of pain, nausea and more.

It is not always easy to predict when patients approach their last few months (end-of-life treatment is defined as the last twelve months; hospice care is eligible for patients that have a life expectancy of six months or less). Decisions can be changed at any moment (if possible). Palliative and hospice care don’t mean that the patient has given up. Sometimes patients don’t start such care early enough to take full advantage of it.

Often overtherapy (more below) at the end of life results not only in unnecessary suffering, but also in lawsuits (most of the time: my loved one has suffered unnecessarily against we have done everything we could and should have) against doctors and/or burden, frustration, guilt and stress for family and carers. If the decisions are already made by the patient him/herself and early education such problems can be minimised. End-of-life care should never be economic (unfortunately, reality is different).

Future plans and decisions like these, along with other documents (living will ‘Patientenverfügung’, lasting power of attorney and guardianship directive ‘Vorsorgevollmacht’/ ‘Betreuungsverfügung’ etc)** should be thought of, talked about and written down early on. For example, which type of care you want to receive when you are terminally ill/severely ill or/and cannot communicate on your own anymore (parenteral nutrition, feeding tube, ventilator etc, also organ donation), whose responsibility it is to decide about further issues and a trust person who is in charge to represent you (ideally somebody you trust fully and somebody who understands your preferences and views – otherwise an external caregiver will be chosen).

There is no right or wrong, decisions depend on the patient’s and family’s preferences only. One should think about questions like these early on:

What do I want in the last months of life? Do I want to have no pain/little pain? Live in comfort? Or do I want to try all treatments that may sustain life? Who should decide when I am not able to do so anymore? Where do I want to live during my last months? What treatments do I agree to? Artificial feeding, ventilation? Or do I want to stop voluntarily eating and drinking? Do I agree to CPR? And what about palliative sedation? Whom do I want to have near me? What about financial issues? Who should take over care of my pet(s), my house…?

When is a life worth living? What is our will (when is a will really free?)?...

Many people don’t want to die, but rather don’t want to continue life dependent on the illness.

Over- and Undertherapy

More treatment is not always better. In some illnesses there is no further positive effect when applying yet another treatment and sometimes it is not necessary when no symptoms/illness actually present. Overtreatment is defined as (a) medical intervention(s) that has/have a very low probability of beneficial effects (no symptom relief and/or prolonging of life) and/or is against the wish of the patient – it is unnecessary treatment without indication.

Nonetheless, overtreatment as well as overdiagnostics (that naturally lead to overtreatment in the sense of treating some norm variant where illness is simply not present because more tests also means that one finds more possible pathologies***

are both massive problems – especially in developed countries such as Germany and the US.

Both, overtreatment and -diagnostics can put a significant burden on the health system (waste of resources and investments which again have a negative effect on general health) and can even harm the patient physically and psychologically.

Examples are the prescription of meds such as antibiotics in viral infections and opioids in pain management, medical treatment of ADHD in children, surgeries such as uterus removal, excessive overtreatment in breast cancer (Kaiser Health News), ovarian operations in Germany (the suspicion of malignant disease confirmed in 10% of cases only) and also orthopaedic surgeries which could have been equally (if not better) treated by physio, long rehabilitation stays and time.

Moreover, many treatments are quality-of-life options and not necessities, but wished by the patients.

Proper scientific guidelines may help the doctors to decide which type of tests are needed or which type of therapies should be applied in what order. Often, however, these guidelines aren’t practical and patients undergo unnecessary testing just because some guideline tells so. Then, there are white gaps, especially in rare cases where no guidelines are present (for example, vascular compression syndromes

which lead to extensive surgeries before sufficient diagnostics and/or conservative treatment options have been tried).

Another cause of overtreatment are false diagnoses because of miscommunication and misinformation, wrong evaluation of testing, insufficient records and so on. Many patients run from one doctor to another to find the right cause of condition, meanwhile undergoing unnecessary treatments and accumulating possible causes that may explain symptoms.

Further causes are the lack of knowledge – both on the side of the patients and doctors, economics, fear of lawsuits/fear of malpractice if not all therapy options have been tried and also pressure from patients. Obviously, they are desperate for help, but often cannot see the situation objectively and by no means have the medical background. Doctors and patients should decide together what treatment should be done and guidelines should be followed.

When I talk about unnecessary treatment or diagnostics I also talk about possible risks and side effects, both short- and long-term. Whether it is nerve damage from frequent radiology imaging, inner bleeding from surgery, severe reactions due to drug-drug interactions or the psychological effects from further stress and uncertainty to PTSD. Every treatment has its (side-)effects, needs follow-up interventions etc.

Too many interventions and trials can do more harm than having done ‘nothing’ (which is no active intervention, but there is still space for monitoring, passive waiting for healing which does take time). But how can we anticipate the success or failure of therapy options in complex or rare diseases? CIPO is rare , having had several major surgeries including quite extensive and exotic ones makes it more complicated and along with further conditions such complexity is beyond a doctor’s ability or any data from stats or publications.

It is a problem of decision for both the patient and the doctor. Depending on the severity of symptoms and quality of life, experimental therapy options might be the only ones left.

Sometimes one doesn’t know the point where to stop. Stop trying. Is there still a small chance that a therapy might work? Shall we give it a try despite possible side effects and/or risks?

There are cases where definitely all therapy options have been exhausted and the path follows palliative care and/or in terminal illnesses end-of-life care. Patients that might have exhausted all options, but still cling to the one possible option. They keep fighting – a fight that they might have lost already or a fight that they might be able to win in the end.

Overtherapy within the end-of-life-care is equally distressing.****

A large proportion of patients dies in hospitals or spends a lot of time (of the last time on earth) in the clinics, undergoing countless interventions. However, many patients actually prefer to stay at home with their loved ones. As already mentioned, tube feeding, ventilation or other interventions as well as non-beneficial tests may not be wished. This is often the case in chemotherapy, radiology and serious chronic conditions where the line to terminally illness isn’t sufficiently clear.

Then, for other patients it is important that all treatments that may give some relief of symptoms and/or sustain life have been tried – no matter how little the evidence is. Overtherapy at the end of life can be circumvented with proper guidelines and support in decision making (the earlier, the better – the more the patient has deteriorated the more difficult it is to decide). Hence, take your time and think about how and where you want to die. Discuss your views with your family and doctors. Doctors should honestly inform the patient and his/her family at the right time about survival time, shift towards palliative/end-of-life care and a system of support should be established as soon as possible. Doctors and nurses should listen to the patient’s wishes and adapt treatment accordingly.

In rare diseases it is often difficult to know when a patient is left with no treatment, because of the lack of data. The right diagnosis is often made after years of wrong diagnoses including unnecessary testing and interventions. Thus, research in rare conditions is crucial to minimise the issue of overtreatment.

Overtherapy brings unnecessary costs, possible risks for patient and doctor/clinic, side effects, even deaths. Actionism is not always necessary. Sometimes our body can heal itself with a little patience. An extensive consultation can sometimes be a better treatment than the prescription of xy.

Ideally, the system needs some deep-rooted change along with good communication skills and knowledge. During important decision making one should always ask for a professional second/third… The Bertelsmann study recommends that doctors should take more time for the discussion of benefits and risks.

Further potential solutions are the easy and full access to health care records and the improvement/addition of guidelines (more practical, extension to rare conditions etc). Often overtreatment and -diagnostics result from the different interests involved (patients, doctors, health care, economy, state…individuals vs state meaning autonomy vs outcome/balance cost & risk).

Doctors should never follow the patient’s pressure or decide on emotional baselines or offer treatments due to the economic pressure on the clinic. It may be of help to follow important discussions in teams of doctors and/or ask an external team of experts to check whether a treatment is truly necessary, especially for high risk interventions. The Choosing Wisely campaign provides lists of interventions that have been often proven to be unnecessary and supports patients in their decision-making process.

Some patients that prefer some kind of treatment to endless waiting, should change their perspective. More mental support may be of help.

Nonetheless, if the health system changes towards a more individualised treatment where the quality of life is of highest priority a lot of overtherapy should be eradicated already. Better and more specialised research may improve the analysis of screening (abnormality pathologic or not?, better predictions and evaluations of harm).

The Taboo of Death

If we want to minimise overtreatment at the end of life, improve palliative and end-of-life care and raise awareness about these topics, we need to start thinking and talking about important questions and death.

In Western culture we are afraid of death and dying. So we simply don’t talk about it. Without advance care planning loved ones will undergo helplessness and guilt, the dying person may spend his/her last days in discomfort and loneliness. Healthcare professionals should support families and take away the fear and anxiety that comes with the topic.

Everybody dies. Death is as natural as birth, illness or love. We should open up and be curious about death itself and think about what it directly means to us individually. How do I want to approach death?

Death is beautiful. We have a limited time on earth where we can wonder and wander, create and change, grow and love, spread compassion and joy… Make the most out of it. Be grateful for life.

The fear of death is related to the fear of the pain and suffering before death and the fear of the unknown, the loss of control and the fear of non-existence/nothingness (which cannot be imagined as consciousness is necessary for experience). Personally, I worry about the people I love and that love me.

How to accept/reduce the fear of death:

- Palliative care can take away (most) of the pain and suffering if you want. There are treatments that provide relief for pain, nausea, shortness of breath and more.

- Don’t fear the unknown. Be curious.

- Concentrate on the things you can control. For example, your wishes and preferences of end-of-life care.

- Talk with your loved ones about your fears.

- Fear is natural. Death is natural. Find ways to accept that fear. Seek professional help (talk therapy, CBT…). Meditate.

- Some find support in religion and its community.

- Be aware and mindful at every moment. Choose wisely.

- Epicurus might advise: When you are alive, death is nothing. When you are dead, life is nothing. Think about it.

- Be grateful for life. Be grateful for the little moments.

- Have a purpose. Work for that purpose every day.

- Take it with humour.

- Participate in death-related projects (experiences with death, dying, grief, loss…), for example, in schools, ‘Wenn Kinder nach dem Tod fragen’, ‘Gib mir´n kleines bisschen Sicherheit’, ‘The Dying Matters Community Grants Programme’, ‘The Truacanta Project’ or cultural projects such as #sterben-tod-trauer-2045 and the ‘Project on Death in America’, ‘Death in Art’ and and the ‘Death and Alive Project’.

Within certain limits fear of death is completely normal. If death or related topics cause extreme anxiety, however, you should seek professional help to reduce that anxiety and accept the inevitability of death.

One clings to life although there is nothing to be called life; another clings to death although there is nothing to be called death. In reality, there is nothing to be born; consequently, there is nothing to perish. (Buddhist quote)

Now having improved overtreatment and saved a lot of money and resources, we turn to the exact opposite.

Another major problem is undertreatment (and underdiagnostics which again leads to undertreatment since pathologic variants cannot be found without sufficient testing) i.e. insufficient treatment both in quantity and quality. Undertreatment is both dangerous in chronic illness since it accelerates it and in acute conditions due to the high risks (for example, coronary artery disease could have been prevented in a large number of patients by early diagnostics). Possible causes include delayed help-seeking and delayed treatment, mistreatment, medical self-care, negligence (see below).

In many underdeveloped countries, undertreatment results from the lack of resources, knowledge, medical training and doctors and nurses as well as poor health care systems (treatment against private costs only). Over half of the world’s population lack access to primary health care. Developed countries should support such countries with medical training and peer review, financial help and resources. Moreover, they suffer from population explosions, poverty, hunger, climate extremes etc that all contribute to illnesses (easier ways of viral infection to spread, general poor health, malnutrition/ low weight, poor quality of life, poor access to hygiene, poor education, no (drinkable) water, poor social structure, lack of infrastructure and so on). People are dependent on local health care or folk medicine. Therefore, help in general infrastructure, education, politics and reductions of poverty, hunger etc naturally lead to better health and improved conditions for health care. As usual, support for self-help is always more efficient (e.g. training of local medicals rather than sending professionals from developed countries that take their knowledge and skills with them when they leave; encouraging local/national structure changes and so on).

In highly developed countries lack of resources and healthcare workers can be a huge problem, too. GPs are overwhelmed and simply lack time and resources to treat each patient fully.

Mistreatment is also a form of undertreatment when the actual condition is not treated or intensity and/or time of treatment are wrong. This can not only lead to unnecessary suffering, but even death. In some cases patients may seek help too late, because they don’t take symptoms seriously or are afraid of possible diagnostics or medical care in general. Other patients decide to treat themselves without any medical background, following some healing tips from the internet.

Over- and undertreatment and/or over- and underdiagnostics can occur individually or coexist. Modern medicine overtreats healthy people and undertreats the sick. Prescriptions are easier and cheaper than complex consultations and treatments that are built on time, resources and patience. A patient with a broken hip may be advised to undergo several surgeries and take pain meds (overtreatment) rather than physio, daily exercising and further conservative options (undertreatment).

We can only minimise both when we change the system to provide maximal (individual) support for the patient and the clinicians, improve communication and transparency, invest in research and proper guidelines and balance interests. The healthcare system should reward doctors for quality rather than quantity of medicines, diagnostics or interventions and should provide a suitable environment and support (communication, organisation etc) to minimise over- and undertherapy.

There is negligence, medical gaslighting, lack of action despite obvious signals. Patients that have real symptoms and are dismissed or downplayed by doctors can lead to false diagnoses, lack of treatment which is needed to sustain life or improve quality of life.

Disproportionately, neglected patients are female, older perople or rare minorities. Sometimes it might not be obvious what’s wrong, many illnesses are not visible – when further scans, blood works etc don’t reveal any pathologies or can’t explain the patient’s symptoms, medicals often stop their diagnostics. Patients don’t feel believed/are not believed, their symptoms are ‘psychological’ and/or patients should simply ‘reduce stress’. However, patients are desperate to find a reason that may explain symptoms. With a diagnosis it is far easier to find the right treatment. For example, there is a wide range of causes for motility disorders. Diabetes can cause gastroparesis years before it is diagnosed. Enteric nervous system damages (here, here, here and here) lead to abnormal peristalsis. When the ENS suffers from an autoimmune ganglionitis immunosuppressive therapy might treat the nerve inflammation and/or slow down nerve cell death. If the ENS, however, suffers from congenital hypoganglionosis due to a genetic effect there is not much one can do other than symptom management. The whole GI tract can suffer from dysmotility and different organs need different treatment accordingly. Thus, it may be useful to have specific neurogastro testing in order to find the affected organs. For example, patients that have gastroparesis with a fully functioning small intestine may benefit from a feeding tube (NJ or PEJ i.e. a tube that either goes through the nose or abdominal wall into the small intestine, hence, bypassing the stomach). Whereas, patients that suffer from a slow colon only need motility stimulating medication, food adaptations, enemas and in severe cases an ileostomy to bypass the colon. People that have IBS are recommended to eat healthy (for additional SIBO, low fodmap may help) e.g. whole grain bread. However, the stomach of someone with gastroparesis would have severe problems digesting this. And so on.

Unfortunately, patients that suffer from rare, complex and/or yet-to-be-understood illnesses often experience negligence because of the doctor’s insecurity and lack of knowledge.

Back to medical negligence. Medical negligence is defined as suboptimal/standard care that might harm the patient and/or worsen the illness. It includes under and/or maltreatment and/or misdiagnosis, but also medical gaslighting. Cases range from practice/administration of treatment without consent of the patient over treatment without sufficient qualification of the doctor and passive negligence (failure to diagnose, monitor or treat) to death due to wrong surgery or improper medication and more.

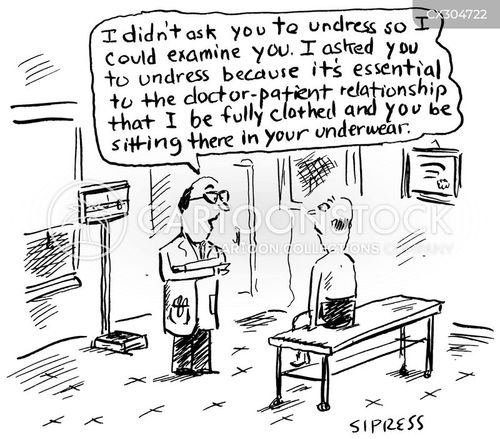

As a patient we trust doctors. It is a civil right to get the right attention from doctors. However, there are black sheep everywhere and some doctors use psychological manipulation that leads to medical negligence as well as doubt, helplessness, insecurity, hopelessness and anger in the patient. Medical gaslighting is a term that describes the dismissal of complaints, symptoms, feelings or concerns. It negatively affects the physical and mental wellbeing of the patient.

How to spot medical gaslighting and what to do about it:

- the doctor doesn’t let you talk and/or disrupts you

- the doctor rushes you through a conversation or treatment

- a rude behaviour towards you

- there is no proper examination or insufficient further testing

- the doctor questions your symptoms or even refuses to hear about them

- the doctor has prejudices because of your background and/or shows racial or gender biases

- ‘your problems are psychological’ without having examined this, ‘It’s all in your head’

- the doctor questions the honesty of your medical history

- the doctor forces a treatment on you rather than discussing it with you and collaborate with you and other doctors

And how to combat medical gaslighting:

- advocate for yourself or take someone with you who can do that (a support person, some professional advocate…)

- be persistent with your concerns and focus on the most important

- professional advocates, seek help at external institutes that can evaluate your situation or you can turn to if you have specific claims (Bundesärztekammer – ‘medical association’ etc)

- keep your notes and records for evidence and managing the conservation

- take notes during the appointment (or ask your relative/friend to do so)

- ask questions (list them beforehand) – never feel ashamed, ask as many questions as you want

- name your issues (also of gaslighting), sometimes there may be a communication error only

- if things don’t change, simply see another doctor and/or get a second opinion (especially in rare illness, ask for a referral to a specialist)

- appeal to higher authority (the chef of the doctor, or even levels higher up)

- trust your gut, get to know your body, be aware and honest

- take your health in your own hands (minimise stress, practise mindfulness, eat healthy,…, inform yourself about your illness and treatments, connect to others that suffer from similar,…), don’t blindly believe and follow everything that is recommended by your doctors

- have a little patience and understanding, too

More advice can be found here. There is the possibility of legal malpractice claims to ask for compensation (care in the future, financial support…) and justice (warning, court,…) if direct harm has occurred. It is very important to keep proofs and work with a professional body (qualified medical lawyer, professional advocate). Everybody should be treated with the right care, dignity and respect. Everybody deserves to be heard and listened to.

‘Greater severity of disability and loss of psychosocial resources associated with the chronic medical condition may lead to psychological disturbances including depression, anxiety, and stress’ (PMID: 9300512) – often patients suffering from physical illness develop further psychological issues BECAUSE of the strain of the illness, the lack of treatment options and understanding, because of medical gaslighting and the lack of medical, mental and social support. Recognising the order of events is very important in treatment (and diagnostics). It is important to provide additional psychological support if needed and psychological diagnoses along with physical ones are possible. However, doctors should always exclude all physical causes beforehand since their treatments are totally different.

Often undertreatment is present in pain conditions (see my past post) since it needs multidisciplinary, individual, flexible and constant care. It is always easier to prescribe than to have a complex consultation which is needed to find the proper path in pain management. There is no objective measurement or evidence of pain and often there is no exact cause for it. Everybody deals with pain differently and often doctors simply don’t believe the patient’s amount of pain and/or are afraid of a suitable drug prescription because of the risk of drug abuse and/or dependence. Pain is an invisible symptom and can become an invisible disease. Chronic pain is often undertreated due to its complexity, elderly suffer from undertreatment because of the misconception that pain may become a normality or lack of cognitive function and communication, minorities of race and women experience undertreatment along with medical negligence. For example, many clinicians believe that women are oversensitive to pain and/or exaggerate in their communication; in acute pain e.g. after surgeries often they receive pain medication a lot later and/or less in quantity than men (e.g. in coronary bypass surgery women are half as likely to receive pain meds); women are more likely to be misdiagnosed with a heart attack since their pain is not believed… Our system favourises the biomedical approach where pathology is prioritised rather than quality of life. Patients that suffer from psychological conditions such as depression are worldwide undertreated. One of the reasons is that it is more difficult to verify mental problems rather than some physical damage. Another is the feeling of shame or fear on the side of the patient who decides not to see a clinician. Better awareness of the importance of mental health would work against this issue. Further, the distinction between physical, somatic and mental health care should be smoother and the access to care programmes should be improved. Generally, functional and/or somatoform syndromes often lack necessary seriousness. Paralytic and mechanic subileus states show very similar symptoms, yet it is the mechanic ileus that needs urgent treatment because of its risks. However, pain, nausea and other symptoms are quite similar (I have experienced both quite often).

Rare diseases are rare, but they do happen. Unfortunately, many patients suffering from rare conditions lack medical treatment options and/or don’t feel they have sufficient social and mental support and lack help for daily life. In fact, only about 10% of people that suffer from rare diseases actually have treatment options that work. When a cure is not possible anymore, patients should have at least access to optimal care that provides relief from symptoms and improves quality of life.

Even when therapy is available in rare illness patients, often they are still left with very distressing symptoms. More interdisciplinary medical work and teamwork between patients, doctors, carers and across levels is needed. Again, a more individualised approach and more awareness are crucial.

Even when nothing can be done, one should at least try to acknowledge the symptoms and provide some kind of help (whether it is raising more awareness, social or mental support, more research in rare illnesses etc).

Lack of guidelines and data make it difficult to provide therapy options. Sometimes it might be necessary to use drugs off-label or apply some experimental therapy even without sufficient evidence and/or despite known risk. Doctors and patients should discuss the risks and benefits. Medical guidelines should support decision making in diagnostics and treatments in medical care based on medical evidence (statistics/data, research) and state-of-the-science knowledge and reviewed by appropriate qualified committees******.

Some of these guidelines include algorithms that simplify the path of possible options a lot. Doctors should then decide whether to follow these recommendations based on the individual patient. In order to do so, they have to adequately monitor the patient and collect sufficient data. Patients on the other side can inform themselves about possible diagnostics and treatments such that they can be included in further planning and gain some autonomy and knowledge.

Doctors and nurses should be aware of the guidelines, suitable teaching and workshops are necessary. Guidelines should be updated and adapted as research improves and statistics change/are available. Moreover, guidelines should be practical. However, often they suffer from conflicts of interest (economic interests shouldn’t play a role, but often opinions are based on them) and too broad or narrow focus (inflexibility, for example, harms the patient). They vary between countries and often miss a formal way of updating. Rare diseases lack guidelines at all and alternative treatment options are often negatively biassed. Further, doctors should follow recommendations, but should keep their mind open. There have been guidelines in the past that were simply wrong and there might be wrong guidelines out there today.

Guidelines help to minimise unnecessary treatments and diagnostics, hence, overtreatment/-diagnostics and its associated harms. They also provide recommendations to follow (both for the patient and doctor), thus, minimise undertreatment/-diagnostics, too. Further, guidelines can reduce medical negligence as it will be more likely that patients are treated according to sufficient standards (definite knowledge on the side of the doctor and empowerment on the side of the patient). Lastly, clinical guidelines in pain management (for acute pain e.g. after surgery and accidents where time is quite limited and chronic pain) should be reviewed, updated, adapted and/or expanded to reduce needless suffering and the risk of chronic pain development as well as improve quality of life. The easy and transparent access to guidelines, both for patient and doctor, via online data banks provide security (key word opioid crisis, drug prescriptions), education (pain is often a symptom along other comorbidities, most doctors aren’t specialists in pain management) and a platform for individualised care for complex pain patients and for an effective triage. Again, they should also include alternative approaches such as mind-body work, cognitive reframing (some references here), TCM and more.

Examples:

- S3 Leitlinien für Motilitätsstörungen

- ESNM Guidelines for motility disorders

- parenteral nutrition ESPEN and ASPEN guidelines

- More German guidelines

- International guidelines for common diseases e.g. by MFS (see also essential drug guide) and WHO, international general guidelines (guidelines from all over the world, published/in development/planned/adapted etc)

- UK pain management guidelines and further

- More general information

The lack of psychological and social support as well as the missing understanding due to lack of awareness and knowledge feel like undertreatment for many patients. Furthermore, often complex patients need more supportive and individual care. The health care system cannot fulfil these needs.

The gap of (perceived) undertreatment is filled with networking between us patients and self-education and/or -treatment. We understand each other, share our experiences and can recommend treatments, doctors, clinics and anything that brings relief. Support groups are extremely important for rare illness patients. However, they can also be dangerous when these recommendations are taken more seriously than medical advice. There is no treatment that works for everyone. Every patient (even with the same diagnoses) reacts differently to medical care. Be aware, don’t believe everything without evidence, don’t get lost in an isolated ‘illness bubble’, don’t follow medical advice from the internet at home,… there are benefits and dangers.

Nonetheless, even patients with different rare diseases share generic burdens and needs. It is totally understandable to look for and provide help. Support groups (in person or online) Benefits include the promotion of inclusion, improved self-esteem and security as well as an increased value in life. Mental (with that, physical) health can improve and acceptance of the illness might be easier (‘I am not alone’). Patients not only share medical advice and how to combat symptoms, but also recommendations for daily life which can only be collected through experience. Moreover, members experience socialisation (many patients are bed/house-bound and cannot take part in social activities) within an understanding and empathic environment. I am in contact with some other patients that suffer from similar issues like me, have undergone similar surgeries and/or share the hopelessness, frustration and uncertainty of illness. With some of them I have become friends, we share our feelings and encourage each other and I am very grateful to have them. Support groups carry risks from inaccurate or miscommunicated information to emotional entanglement (when others suffer, undergo emergency situations, have died) and isolation from real life where the illness takes up all space. In the past years I have come across several online accounts where patients not only raise awareness and/or share their experience with chronic illness, but fully identify and become obsessed with it and make it their life. In my opinion this isn’t healthy at all. There shouldn’t be any competitions about sickness, exaggerating or false illusions which all carry the risk of harming others. Support groups can also suffer from tensions and/or emotional discussions which aren’t easy to digest. If you have followed my posts you know that I raise awareness and share information about vascular compression syndromes because of my own and others’ experiences. Many patients have been searching for a diagnosis for many years, connect via the internet with miraculously healed patients via extensive surgery, they all share 10+ rare condition diagnoses (from the same ‘doctor’) etc and finally end up with same problems: symptoms have not been resolved or worsened including an increase in GI dysmotility. Wrong and/or unrealistic hopes are raised (similarly, false fears can arise). We can’t save everyone. Lastly, In such groups the negative parts often dominate or people just want to unload (I have xy problem, abc new symptoms, what can I do?, does anyone else have xy?, I can’t go on like that anymore etc) – patients become more aware and sensitive of possible symptoms and negative feelings and lack the positivity that life brings, too.

It is important that some objective admin checks for possible misinformation and further risks and if needed intervene. Participants should follow rules/guidelines that allow a safe and balanced communication exchange. You aren’t responsible for anyone else as long as you stay honest. Group programmes as in outpatient pain management clinics or talk therapies led by professionals and in person have definitely shown major benefits for patients. If you are part of (online) support groups and cannot carry the emotional burden, feel anxious, depressed or even suicidal, please look for professional help. Talk to someone you trust, a medical professional (your GP, psychologist,…) or call/text a crisis team.

US help

- dial 988 or 1-800-SUICIDE

- crisis text hotline: text HOME to 741741 https://www.crisistextline.org/

UK help

- Call 116 123 (Samaritans) https://www.samaritans.org/

- Call 0300 1020 505 https://sossilenceofsuicide.org/

- Call 0800 58 58 58 https://www.thecalmzone.net/what-we-do

- Text “SHOUT” to 85258 https://giveusashout.org/

Germany help

- Ruf 0800 / 111 0 111, 0800 / 111 0 222 oder 116 123 an

- https://www.telefonseelsorge.de/

Further advice in English and German. Information on signs of depression and suicidal thoughts in chronic illness can be found here and here.

In illnesses without cure, degenerative ones with poor prognosis or rare diseases one should at least find a therapy that reduces symptoms in a way that one can find life outside the illness and not only fights for survival each day. One could try to reduce the emergency situations by proper monitoring and/or make it possible for the patient to live/spend time at home rather than in clinics.

We need some support, some stability.

To give an example for the above mentioned (therapy, over/undertreatment and -diagnostics etc). I was diagnosed with a motility disorder in 2017. Unfortunately, we (doctors) didn’t look further into this issue (underdiagnostics leading to undertreatment: severe malnutrition, pain etc and desperation) and so I underwent a very extensive surgery of vascular compression syndromes which resulted in many complications that needed re-interventions and/or have long-term effects on my health. Diagnostics and treatment of vascular compressions aren’t listed in official guidelines. Whereas I probably did suffer from MALS, I was also treated for NCS and MTS with rather invasive methods (overtreatment that ironically led to an artificial NCS that needed treatment as well as an aneurysm that had to be resected. In the meantime my actual underlying condition has developed to now end-stage intestinal pseudo-obstruction.

CIPO patients should undergo as little interventions as possible because of the risk of further nerve damage and additional mechanical issues (adhesions, mechanical ileus states) of an already very fragile system. Unfortunately, most of us have undergone surgeries and many interventions due to false diagnoses, maltreatment and exploratory surgery (paralytic ileus states that mimic mechanical ones) because of the lack of knowledge of this rare disease. We have exhausted all therapy options except a high-risk intestinal transplant which might provide a few years of better life quality. At the moment I am not transplantable, palliative care also has its limits and so I am left with very distressing symptoms.

I am waiting for something to happen. But doctors simply cannot do much/anything. They can treat emergency situations and they can try to stabilise me. Phases of constant stagnation or slow progression are equally frustrating. Long periods of waiting grow uncertainty and take up a lot of energy. I can’t therapy myself and need others to make decisions, but no one wants to take over control. Referrals here and there. Every clinic/doctor follows his path and treats his/her part of illness (neurology, gastroenterology, vascular expert, angiology, dietician and so on), interdisciplinary teamwork, communication and collaboration are rare. Some are waiting for the others to take action, some are interested without providing support, some simply don’t want to risk anything (passive action, medical negligence). Between palliative, under- and no treatment we don’t know whom to turn to anymore. At home we have all kinds of (iv) meds, monitoring devices and what I need for daily survival. One of our rooms is basically a pharmacy, IMC/ICU storage room, sterile TPN prep, palliative care ward etc. My mum is the best caregiver and we are fully trained in the administration and care of TPN, ileostomy and co. Nobody else (including the medical teams) is aware of the suffering. Nobody else sees our daily struggles. In fact, we feel (are indeed?) left alone. As the illness has progressed and got more complex in the past years, this kind of isolation has equally increased.

I am dependent on treatments, symptoms (and symptom control), diagnostics, reports, phone calls, test results, prescriptions, bureaucracies…for every step. Every day we wait for what will happen and we wait for something else to happen. Nowadays we cannot even tell what we are waiting for. Sometimes I feel stuck (have a look at my poem ‘Stillstand‘).

Waiting leaves me in uncertainty that opens up hope but also fear that nothing will ever change.

Further evidence for over/undertreatment from the literature are given in the following case reports:

- “Please, do not make us suffer any more…” Access to Pain Treatment as a Human Right, 2009 → poor availability and access to adequate pain relief

- ML Maciejewski et al, ‘Overtreatment and deintensification of diabetic therapy among medicare beneficiaries’, 2017, J Gen Intern Med 33: 34–41 → Diabetic treatments leading to cardiovascular events, cognitive impairment, fractures and death

- F. Rozza et al, ‘Is there a risk in overtreating a hypertensive patient?’, 2017, J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 18: e50–e53 → Aggressive hypertension treatments can cause hypotension with further severe side effects: acute renal failure, hyponatremia, hypokalemia and syncope

- E. Gozzi et al, ‘Undertreatment with Osimertinib in patient with multiple chemical sensitivity. A case report’, 2022, → Undertreatment, because patient decreased drug dose; still leading to sufficient result

- RS. Wiener et al, ‘Time trends in pulmonary embolism in the United States: evidence of overdiagnosis’, 2017, Arch Intern Med 171: 831–837→ more sensitive imaging leads to an increased treatment of potentially benign pulmonary emboli

- J. Heck et al, ‘A case series of serious and unexpected adverse drug reactions under treatment with cariprazine’, 2021→ Unexpected drug-drug interactions, need more monitoring (example for undertreatment)

- O. Bassat et al, ‘Chronic pain is underestimated and undertreated in dialysis patients: A retrospective case study’, 2019 → Chronic pain undertreated in dialysis patients

- PMC5587107 → reasons for overtreatment in the US: fear of malpractice, patient pressure/request, difficulty accessing medical records (mainly physicians were asked though)

- D. Baba et al, ‘A case report of Kuttner tumor mimicking a malignant tumor, leading to overtreatment’, 2021 → Kuttner tumor mimicking a true malignant tumor resulting in overtreatment

- Doi: 10.4045/tidsskr.15.0630 → Antibiotics for infection resulting in overtreatment ‘He received unnecessary treatment, experienced side effects of the treatment, and then experienced side effects of the treatment for the side effects. Rare too is the authors’ bravery in exposing their own judgements and choices that turn out to be flawed.’

Patient Doctor Communication

As already mentioned above, patient-doctor communication is crucial for the improvement of medical care and the doctor-patient-relationship.

Detailed information can be found below.

How to talk to your doctor:

- Be prepared (e.g. a list with questions, meds, symptoms, your history etc)

- Be organised

- Be scientific

- Ask questions, especially when you haven’t understood something – don’t save them for the end (you will have forgotten them) or leave without full understanding

- Be interactive

- Be honest and open (doctors cannot read our minds)

- Have someone with you who can emphasise the situation, talk when you are unwell, support you etc

- Take notes

- Listen

- Leave a message

- Share everything (especially in diagnostic searches): Symptoms, lifestyle, all meds including natural products, etc

- See another doctor if needed

What I wish doctors would have:

- Compassion

- Quality and knowledge

- Cooperation

- Work ethic

- Empathy, but professionalism (never dismiss any worries of the patient)

- Understanding and caring

- Experience

- Passion

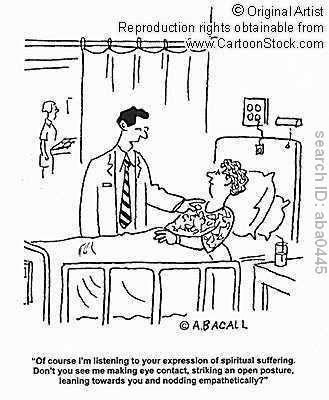

- Communication skills including active listening, not interrupting, clear and credible, nonverbal communication e.g. eye contact

- Honesty

- Confidence, but know where own limitations are

- Good team (meaning good communication within his/her team/ with the secretary, teamwork and organisation skills & the doctor works with with patient)

- Non-judgmental and no prejudices

- Acceptance

- ‘Patient beyond disease’ perspective

- ‘Patient as an individual’ perspective

- Respect

sources: Imgflip.com , smidr.com, dolighan.com, cartoonstock, F. Ahlefeldt, M. Hayward

Good and effective communication improves individual outcomes and general health, provides satisfaction and trust.

Provided doctors have all of the qualities mentioned above, communication skills can be (further) taught (I won’t go into detail about nonverbal communication etc, but will concentrate on doctor-patient communication). Nowadays, medicals undergo professional training for communication skills and interpersonal relationship building early on (further workshops for adaptations and updates are provided at many institutions). Often they follow the AIDET scheme*******: Acknowledge the problem/the patient’s concern, introduce themselves and give an overview of the duration ahead, explain (the diagnosis, treatments to follow, etc) and finish with thank you. Communication (as always) is based on the perspectives, beliefs and views of the doctor and patient. Thus, the doctor should be objective without prejudices (gender, race, background, social status etc). In the past years, along with growing patient’s autonomy and self-education, communication has shifted the patient towards the centre. Doctors ask open-ended questions and try to maximise participation and inclusion and encourage collaboration. An active communication leads to an active participation in treatment and, hence, possibly better health.

Patients usually prefer the psychosocial model of communication whereas many doctors use the biomedical model which results in a discrepancy of missing empathy (most patient’s complaints are about the lack of empathy). Doctors should not only diagnose and treat, but also identify the ‘true’ problems that affect daily life and/or decrease quality of life. Curiosity, attention and active listening is needed here. (Invisible) Social Determinants of health (SDOH) have a complex interplay with the illness and should be understood.

Obviously, during the conversation the topic and message should become clear (what am I diagnosed with? What does that mean for my life? What treatment options are there? What is the cause of the disease? What are the triggers of my symptoms?…). The doctor should understand the topic and only forward right information which should be easy to follow for non-medicals.

A good doctor should cover both clinical and interpersonal care within the right boundaries.

Communication is also essential between doctors, nurses and beyond – so much time and mistreatment could be saved if there were effective updates and information exchange between shifts, referrals and in hospital care. Time constraints, hierarchies, lack of documentation systems and too many specialisations make it difficult to fulfil.

Good communication between the team does not only improve patient outcomes, but the patient and team will feel safe and understood, too. I don’t know how often I had to repeat things (including major diagnoses, allergies etc) during the same admission due to the rotation of doctors and nurses. Forwarding important information is as important as the actual communication with the patient. Missing or false information can lead to false treatments and real harm. I would always advise to repeat important information – just to be safe.

In an emergency situation it may be better to actually treat the patient as an ‘object’ rather than concentrating on active communication (often this isn’t even possible). Complex patients (where the medical knowledge is definitely on the side of the doctor) might be under the guidance-cooperation model meaning the doctor recommends and the patient follows.

Miscommunication can lead to fatal risks and/or emotional distress. In many cases poor communication qualities reduce patient compliance and trust in general health care. In fact, the nocebo effect can arise i.e. bad communication can increase pain and anxiety or other symptoms. Patients may not trust the diagnosis, treatment, doctor or medical institution anymore. Anxiety, fear and further negative feelings may arise and negatively impact the treatment, physical and mental health. After long waiting times for the appointment itself, in the waiting room with major symptoms, patients may walk out of the practice after a 5min appointment without new answers or even more questions.******** Unfortunately less and less time is given for proper appointments which absurdly turns into unnecessary tests or treatments (see overtreatment) and undertreatment/diagnostics. Doctors suffer from time stress and cannot fully concentrate on the patient.

Obviously communication always depends on the environment,clinic conditions and resources such as the available time, money and doctors there are. The appointment room itself should provide sufficient privacy and psychosocial atmosphere. Cancelled appointments, long waiting times, overcrowded waiting rooms, the journey to the clinic etc all have an effect on the patient’s perception of the appointment (although they don’t have any relation to communication itself).

Other problems include language barriers and cultural diversity where it is advisable to have a translator with you. In cultural differences the RESPECT scheme me be of use (Rapport = connect socially, ask for the patient’s perspective, judgement and assumptions aside/ Empathy = understand the patient’s problems and feelings, acknowledge them/ Support = find barriers of care and help to overcome them, if suitable add family members, reassure full support/ Partnership = reassure teamwork/ Explanations = explain and check for understanding/ Cultural Competence = respect the patient’ culture and beliefs, keep in mind that the patient’s perspective is based on the socio ethnic and/or cultural status, be aware of your own biases, find possible cultural barriers/ Trust = take your time, offer a trustful environment).

In general, I recommend having a family member, friend or professional advocate with you. From my own experience I know that often I am not able to talk much, to concentrate the whole time and/or recall everything (despite notes) because of my symptoms. Whether it is for adding important information on your half, taking notes or emotional support. As described above, some doctors might not believe you(r pain/symptoms), but your companion can provide further evidence or support.

An important task is also giving bad news, for example, a life-limiting or -changing diagnosis to a patient or the message of a death of a relative to family members as well as talking about topics related to palliative/end-of-life care. Honest, clear and simple articulation may be challenging, but essential. Healthcare workers should also be trained for these situations. Otherwise false hope or misunderstanding may arise. Patients prefer straightforward yet empathic communication.*********

One part of patient-doctor communication is also taken by telehealth/-medicine (former defines the use of communication technologies to provide healthcare remotely whereas latter can be defined as using telecommunications technologies to support the delivery of all types of medical, diagnostic and treatment-related services.) This includes

- Teleconsultations

- Telehomecare and -monitoring

- Telepharmacy (delivery of medicine through telecommunications without actual personal contact with the pharmacist)

Covid 19 has proven that telehealth is an alternative. Telehealth has lower infection risks and, thus, safer during pandemics and flu seasons as well as for patients with a weak immune system. Often it saves costs for patients and the medical system which can be invested in improved care. Virtual follow ups (where no physical examinations are made) during treatment trials or post op save time on both sides. Patients whose symptoms might increase from the transport to the clinic feel more comfortable and safer in their own environment. The journey to the doctor, the waiting in overcrowded rooms and walking through corridors of other patients that suffer all affect the mental and physical health of the patient. The patient’s communication may be more honest and open. Teleconsultations also give an insight to daily living and doctors may get a better understanding of the patient’s symptoms and concerns and their effect on everyday’s life. Telehomecare provides safe and independent care at a patient’s own home. Both are for everyone including patients in remote areas. Thus, telecare and -consultations are especially advantageous for patients with rare (specialised advice from all over world) and chronic diseases (specialised advice 24h). Patients are often too weak to take care of the collection of medicine. Telepharmacy is a good alternative here, including the reduced risk of infection in the pharmacy. Further advantages can be found below (AI).

Telehealth also has its dangers. Many patients and doctors are concerned about the lack of security and privacy. Communication may be less empathic and caring because of its virtuality and possible lack of nonverbal communication. Doctors fear too much patient empowerment, both may be sceptical about the dependence on technology (equipment might not work or might be too expensive, storing may be lost, connection issues, need for updates, technicians, education etc – consultations or care might not happen at all). As always, it is about the balance, both kinds of communication should be used equally. The younger generation may be more happy to use this kind of alternative whereas elderly may be more reluctant to do so.

With the help of studies that use artificial intelligence (AI), medicine tries to improve patient-doctor communication. It was found that the language used by doctors is too complex for their patients to understand. The studies also uncovered strategies to overcome communication barriers.

AI may not have empathy, but it can analyse a lot of data. Practice of empathy requires time and experience which can be compared to the analysis of a huge variety and quantity of data. The analysis of words and understanding on both sides uncover possible miscommunication. In fact, it was found that AI did provide better communication both in quality and empathy (see the Guardian based on this article).

New technologies can also be used for better documentation which automatically leads to improved communication and saved time.

AI may be seen as a new/third actor between patients and medical care. It can function as a bridge and translate medical jargon between (AI can modify a given set of content into something that any individual can understand, see AI chatbots). It can categorise patients not only according to their symptoms and conditions, but social, educational and cultural etc beliefs and backgrounds.

It increases patient autonomy, hence, improves shared decision making. Further, AI may also improve care support, management, appointment and care plans, distribution of resources… and provides satisfaction on both sides which again improves communication.

Nowadays, there are systems that help in/remind of medication intake and monitor health conditions. Appointments and examinations every few months don’t give accurate feedback and devices can send data to professionals in case of emergencies. Remote monitoring includes blood pressure, heart rate, glucose and other measurements. Many patients also collect their data on smartphones and (AI) systems can help in their evaluation. This not only increases safety due to continuous care, but also the feeling of security and support. Somebody is there that listens and acknowledges (and can provide answers).

Lastly, virtual reality (VR) is nowadays used for training in surgery, education of new medical experts, but also in illnesses such as mental health problems and complex pain syndromes as well as addiction problems. VR can simulate medical procedures to both and teach the patient of his/her diagnosis and possible treatment options in an interactive and understanding way. Intercontinental medical teams collaborate per video on complex patients , in rural areas and developing countries and hold video meetings on complex and urgent situations. In rural areas, specialised surgeries in developing countries. VR can simulate data and make it more graphical for patients’ and doctors’ understanding.

AI improves communication between different medicals and between patient and doctor, education, understanding and satisfaction on both sides. Further, it supports telehealth and can save costs that may be invested in improved care again.

However, its introduction and development into medicine and healthcare should be well thought about. It can’t fully diagnose or take over whole treatments. It shouldn’t be thought of as superior, AI also can make mistakes and interpersonal interactions are essential in healthcare.

Written communication is equally important including doctor letters and effective documentation. Letters function as communication and record for the patient and as information for other doctors (GP, specialised referrals etc).

Templates and guidelines should be followed: a short summary of relevant history, examination(s) and investigation(s) and previous treatments (mostly relating to the presenting complaint/condition)/ a summary of medical comorbidities (including previous major surgery)/ a list of current meds/ a short summary of the patient’s goals and the management plan i.e. a list of recommendations. Latter might be the most important for the patient, it should be clear what the next steps are and whose responsibility it is (What is the current treatment plan? When is the next follow-up? What to do in an emergency? In the case of deterioration?…) Unfortunately, letters often include unnecessary data (less is more) or miss important information. The letter should be directed to the patient, the actual text shouldn’t include much medical jargon (the lists of diseases, therapies, medicine etc should contain the proper medical terms to eradicate any confusion), for example, use ‘kidney’ instead of ‘renal’. Always read the letter carefully and mention any false information (of importance) such that it can be corrected. This is important for your own understanding and record, but also for your other doctors. Sensitive information and/or possible suspected psychosomatic/psychiatric diagnoses should only be included with your consent. In certain referrals this can become important and patients may be not fully believed or prejudices dominate the new doctor’s evaluation.

From my own experience I can say that there are only a few letters that are 100% right (some misinformation you can ignore). Always recall that letters are followed by treatments and misinformation can lead to mis/under/overtreatment. An interesting observation is the difference in letters between the German and UK medical system. The latter includes more personal information (such as: ‘The patient arrived with her mother.’, ‘She had to interrupt her studies.’ etc) and a warmer and more friendly language. To me this is the better way since the effect of the illness/complaints on daily life becomes more visible and the patient feels more welcomed and understood. Because of their dual/multiple purposes, letters often become quite messy. However, letters should be clear and organised. More confusion (on top of the uncertainty from the illness) only leads to negative feelings, insecurity and mistrust on the patient’s side. A huge problem is the long waiting time for letters which patients often need in order to prove recommendations. Therapies won’t start before the letters and sometimes their arrival can take months – months of unnecessary waiting and suffering. I would always advise to remind and/or push your doctors.

Letters are also important for carers and family. Recommendations should also contain medical and/or social care advice.

Obviously, it always depends on the type of medical letter (outpatient clinic letter to GP and patient, discharge letter from hospital, referral letter to specialists etc) which kind of information should(n’t) be included.

Improving doctor letters increases patient care and satisfaction.

Communication is based on trust and mutual consent on both sides.Patients can be very difficult due to their desperation, poor mental health and frightening symptoms, long waiting times and impersonal environment or they simply have a bad day. In some settings, the patients are the problem. They consciously or unconsciously are manipulative, not honest or, force the doctor towards certain decisions. Patients may be threatening, demanding and/or exaggerate dependence. Examples are ‘I am allergic to everything but morphine’, ‘You have to help me. You have to prescribe xy, otherwise I cannot survive.’, ‘You kill me!’ , ‘If you don’t do anything I will contact the police!’. Patients may also forward wrong or lacking information, chaotic records or don’t show as much openness as a full evaluation would need.

Further challenging situations can arise from discrepancies of perception and expectation as well as the emotional status of patient and doctor. A patient may become frustrated that no diagnosis has been found despite testing and distressing symptoms and may make the doctor responsible for it. Another patient may not feel listened to because of the nonverbal communication of the doctor and is then encouraged to follow his/her advice. This doctor may have had a very difficult discussion or challenging surgery before and simply feels overstressed. We shouldn’t forget that everybody is different and has his/her own personality, not everybody can get along with each other. Nonetheless, we should focus on our common goal and find a solution for the patient’s problems.

There is definitely a lack of communication about pain (see my post about pain)**********. How to describe something so complex yet invisible and personal to the doctor? In order to find the right diagnosis doctors often go through a checklist of questions about the quality, intensity, pattern, duration and triggers of your pain. You don’t have to use medical jargon, but try to be as detailed and accurate as possible. It is very important to raise awareness about (chronic) pain. Patients shouldn’t be ashamed or hide themselves, doctors should actively listen and acknowledge the pain. We think that we become vulnerable when we disclose our pain, but it actually shows our strength. When we grow we adapt our language of pain according to our culture, education and social environment influenced by the family and possible events (early illness, trauma/accidents…) – from nonverbal expressions over crying to ‘Ouch’ and further sentences later containing the word ‘pain’ itself. Every culture has its own and unique way of interpreting pain, suffering, life and happiness. Doctors should be aware of their own and the patient’s verbal and non-verbal (pain) communication.

Pain is such a personal (yet universal) phenomenon and our language is simply not made for the transferral of such. Even people with great linguistic ability will have a limit when talking about pain and suffering. Metaphors may be of help, for example, ‘There is a dagger/knife in my chest.’, ‘I am going over burning flames.’ and ‘A ball moves inside me.’. Direct comparisons/Similes like ‘It feels as if I ran a marathon’ or ‘It is just like labor/period pain.’ can also support the doctor’s analysis. Hyperboles like ‘I am dying from pain’ or ‘It feels like a thousand times worse than ever.’ amplify the urgency and intensity. Speaking about pain, using simplifications, metaphors or comparisons improve diagnostics, treatment and outcome as well as our mental health. It breaks the darkness and vastness, takes us closer and simplifies sensitivity and acceptance. Humans love to categorise, understand and describe, we feel safer and in control. Thus, we apply the same methods to pain as well. With our language we can also shift the perspective on pain from ‘enemy’ to ‘protector’, ‘disabling’ to ‘possibilities left’, ‘destruction’ to ‘creation’ and improve our mental wellbeing. For example, ‘Pain is like the weather. Today it may be cloudy and stormy, but the sun will shine again.’, ‘Pain is a teacher. I have learnt a lot about mindfulness, gratitude and life through pain.’ or ‘Pain is my companion. I accept him and we have to cooperate.’. Writing this blog about topics that are important for many including me is also a way of transferring my pain into something helpful and creative.

Pain asks us major philosophical and vital questions.

Language often tells us the meaning of things. What is the meaning of pain?

Based on the non-shareability of pain, Scarry argued that pain is no object and even destroys the language (‘The Body in Pain’) that could relate it to other objects. We can only groan, cry and scream. Doctors, treatment and health system aside this leads to definite suffering without any relief. Pain eradicates everything else. Wittgenstein emphasised that pain also has a social role (communicate between each other, understand situations and reactions etc) which we have to learn. Thus, there is a relation towards the outside world and pain is not a personal entity only and interpersonal interactions have to be accounted for. Pain expression and experience are affected by our language and society (note, Wittgenstein said all languages must be public, private language cannot exist in his opinion). Language (connecting) and pain (destructive) can be complete opposites or in an intertwined relationship. Herder looked into the relation between the origin of language and pain. He comes to the conclusion that our cry of pain is the language’s beginning, but pain may reverse language’s evolution.

Dickinson (usually quite eccentric in her language) reduces this harshness a bit where pain ‘has an element of blank’ only. Still she depicts it as a timeless and individual entity that takes up full existence and dominates life. The poem describes pain vividly (basically personifies it whereas the patient is de-personified and loses identity) and intense and I guess everybody that suffers from chronic pain can relate. At some point pain has consumed us and blocks all other senses. It seems impossible to break that everlasting cycle. Nonetheless, don’t forget the power of perspective and impermanence – the future might provide better days. Don’t become your pain. At times it will dominate, at times you will work together and live with/despite it. You are much more than your illness or that pain. With that, Dickinson has found the language despite its character. You can do so, too.

‘Pain has an element of blank;

It cannot recollect

When it began, or if there was

A time when it was not.

It has no future but itself,

Its infinite realms contain

Its past, enlightened to perceive

New periods of pain.’ by Emily Dickinson

Further poems about mental and/or physical pain by Dickinson (Dying/ It was not death for I stood up/ I felt a funeral in my brain/ After great pain, a formal feeling comes) and others can be found here.

How to describe your pain to your doctor:

- Focus on your sensations.

- Think about its quality: How does your pain feel? Cramping, dull, electric shock like, aching, burning,…, pins and needles, shooting, stabbing, throbbing,…

- Think about its intensity, duration and pattern. Does the pain come and go? Are you always in pain? With spikes in between? If it starts, how long does it take to go down again? Are there any triggers and/or reliefs? How severe is your pain? (Have a look at my post for different pain scales. Understand the pain scales, don’t exaggerate or underestimate.)

- Think about its location: Where is your pain? Is it located at a single point, in an area? Does it spread? Is it constant or changing?

- Prior to an appointment, write down everything you want to tell about your pain. Where do you feel the pain? When did it start? Was there a cause?…How does the pain affect your daily life?

- Start a pain diary to evaluate the quality, intensity, pattern, any triggers etc.You might find something you haven’t been aware of so far. For example, date/pain severity (1-10)/quality adjectives/any triggers before e.g. exercising, food intake, rest etc/any things that provided relief e.g. warmth/cold, medication, rest, moving etc/further.

- Further help can be provided by books, publications and apps e.g. Pathways Pain Relief and Curable.

- Along with your notes regarding your pain also take records about your past pain therapies (pharmacological, interventional, alternatives) and an updated medication plan.

A few examples of communication issues and how (not) to solve them.

Ex 1: A teenage girl with her father comes to discuss birth control options. However, the father doesn’t agree that the daughter wants to be sexually active and wants them to leave.

→ The doctor should explain to both what will happen during the appointment and discuss any medical history. Then, he should kindly ask the father to leave the room such that he can discuss the issue with the daughter alone. Afterwards, the father can come to the end of the discussion.

Ex 2: A patient from another country arrives alone to an appointment and does not understand the language.

→ Ideally, the doctor/secretary should have advised to take some friend/family member or professional translator with him. If the doctor/secretary can’t get hold of somebody who can translate he should communicate as simply as possible (with ‘hands and toes’, google translate…). If needed, the appointment has to be shifted to another date. The doctor should not be angry at the patient or make fun of his/her translation issues. During the appointment the doctor should frequently check the understanding (the patient might be shy or ashamed to ask) and make it as comfortable as possible for the patient to ask questions. Mistranslation can lead to misunderstanding on both sides, wrong diagnoses and/or treatments including the risk of harm (e.g. drug reactions), stress and mistrust as well as increased cost and dissatisfaction on both sides.