Uncertainty – Quantum, Philosophy and Illness

A while ago I watched ‘A discussion with Dr Barry Kerzin* & Prof Carlo Rovelli about Nagarjuna’s philosophy and quantum physics’ as part of the QISS. I would like to share some thoughts from this discussion mainly about Nagarjuna’s philosophy (I recommend Garfield’s translation) and its application to the question of single identity (quantum mechanics aside).

Nagajurna’s middle way is the foundational book of Mahayana Buddhism philosophy. Its central theme is emptiness. Emptiness is the absence of independent, inherent existence. Hence, it is not nothing, but full of interaction – nothing can exist on its own. Fundamental reality has no fixed core, but only interacting bodies (or rather the interactions themselves).

Digression. Barry has often emphasised how resilience can grow through compassion:

Compassion is the wish and the action, when we’re able, to reduce or even eliminate pain and suffering.

Compassion means being aware of suffering and pain around and within me (self-compassion). If we practise our awareness towards others, we can cultivate compassion. Altruistic actions may grow compassion, too. The experience of others’ suffering and the acceptance of suffering will improve your reply to your own suffering.

For me, loving-kindness meditation has helped a lot.

Along with this your resilience will bloom, it will raise new hope even in difficult situations. Take a deep breath in. Think of someone you know or a stranger that has a difficult time. Be mindful. Be kind. Accept this suffering. Be aware of it. Acknowledge and reflect it. Now repeat the same for your own pain.

(Universal) Compassion is the acceptance of suffering, the motivation behind all, it should be our answer towards others and our own suffering, it is the way to mindfulness and awareness. Hence, we are not talking about the feeling of compassion (indeed, it should be without passion and attachment at all), but the constant awareness that everyone of us is connected to everything else and that our thoughts, actions and words have an intermediate and/or long-term effect and similarly arise from the interdependence. It is our wish to reduce overall suffering.

Interconnectedness means everything is related to everything else. All phenomena arise in dependence and relations, under cause and condition.

The middle way is the right path between two extremes, indulgence (blindly following the senses) and deprivation (avoidance of all indulgence), leading to emptiness. Generally, it is the full acceptance to resist any extreme viewpoints or ways of life (recall: appreciate the little things).

Emptiness is reality’s true nature, there is no autonomic entity. Things arise dependent on cause and conditions, everything is correlated and interdependent.

When this occurs, that comes to be; from the arising of this, that also arises

And this connectivity is the root of all suffering (Heidegger would agree).

Back to their conversation, Rovelli talks about his philosophy of relational quantum mechanics (which can also been explored in ‘Helgoland’**) and the wonders that cannot ever be understood no matter how much physicists and philosophers think about.

The theory of quantum mechanics has one of its roots in the summer of 1925 where Heisenberg took holidays on the pollen-free island Helgoland to recover from hay fever. After that he wrote his famous and important work ‘Über die quantentheoretische Umdeutung kinematischer und mechanischer Beziehungen’ (‘Quantum theoretical re-interpretation of kinematic and mechanical relations’) in collaboration with Pauli. Along with Born and Jordan he introduced a consistent mathematical framework (don’t forget Dirac, Einstein and Schrödinger of course).

The use and need of probability theory, the loss of the certainty of knowledge and predictability were new and also frightening – we have serious difficulties in their understanding and especially in their acceptance. In fact, Heisenberg replied to his own work as ‘very uncertain’.***

Uncertainty…

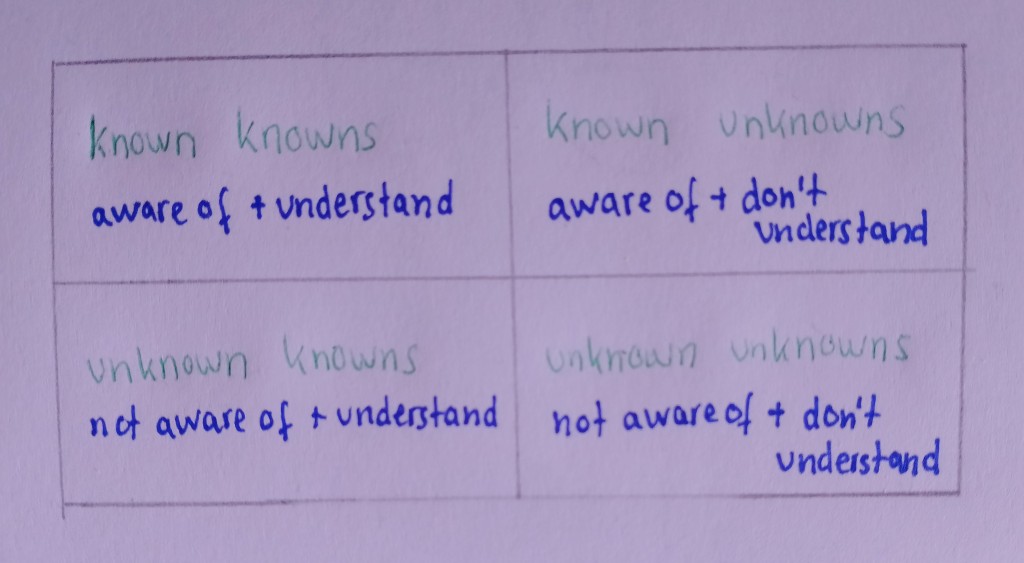

Humans have a major fear of uncertainty. In stressful or traumatic times the pure co-existence of uncertainty can amplify negative emotions even more. We are afraid of the known unknowns as we immediately categorise them as potential threats. Yet we are not afraid of the unknown unknowns. Hence, our experience, our interaction with the world (up to this present moment) influences our reaction towards unpredictable or uncertain situations. The more we face such situations, the more our coping mechanisms develop. We feel helpless due to the lack of control. However, often it is rather the fear of our own feelings that we anticipate such as loss of hope, powerlessness, sadness, grief …****

Uncertainty itself leads to stress, frustration and inability of action (which further amplifies uncertainty again). Only our response to uncertain times, events, and decisions can break this cycle.

(Chronic) illness inevitably raises uncertainty.

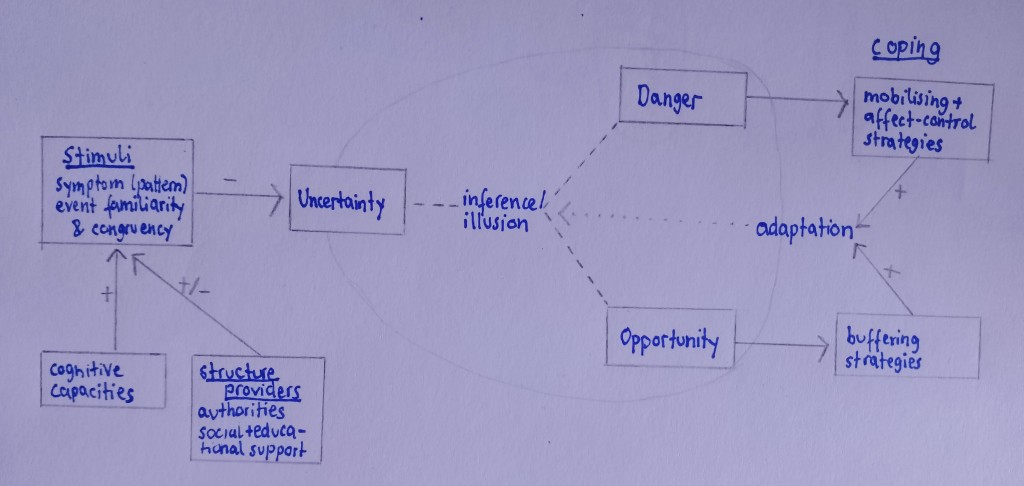

Mishel (1981, 1988, 1990) introduced the concept of uncertainty in illness consisting of four major components: ‘(a) antecedents generating uncertainty, (b) appraisal of uncertainty, (c) coping with uncertainty, and (d) adaptation to the illness’. She defined uncertainty as “the inability to determine the meaning of illness-related events” meaning accurately anticipating and/or predicting health outcomes and its meaning in life.

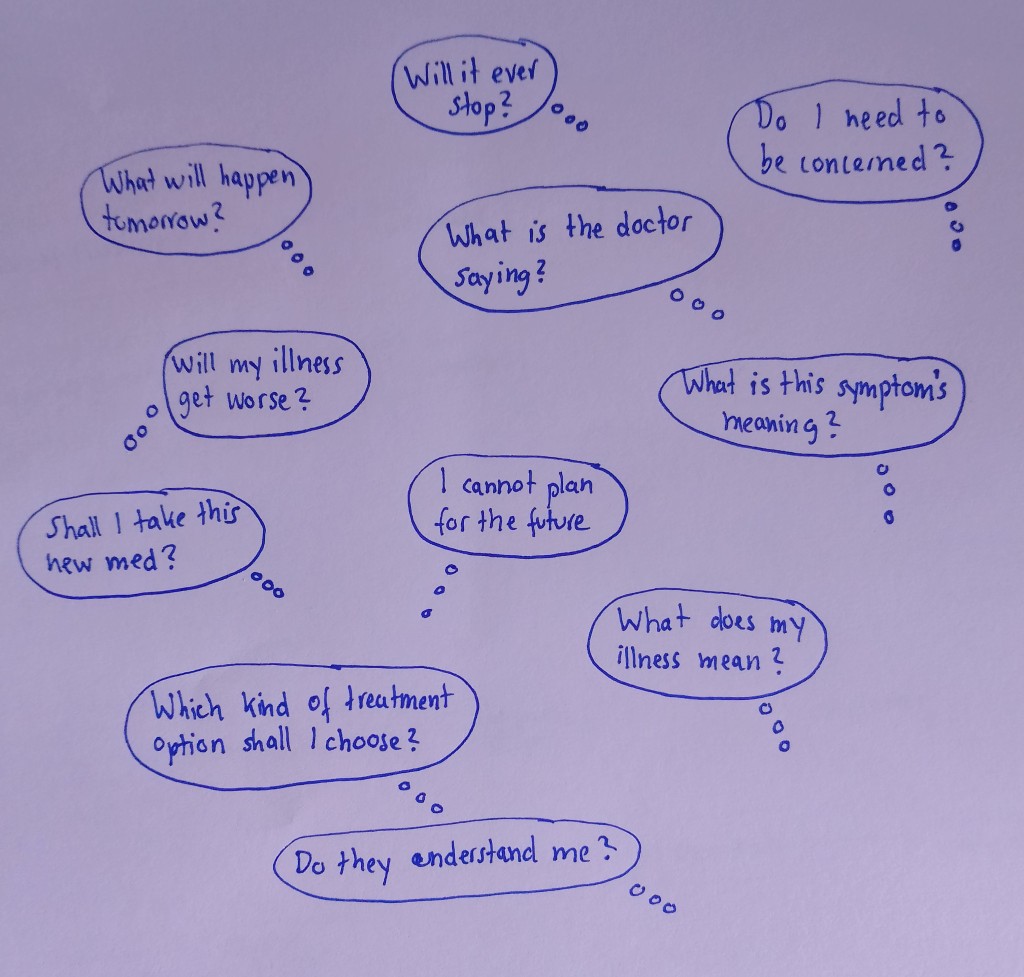

Ideally, the theory should explain how patients should create meaning for the illness or illness-related events (with uncertainty meaning the loss of meaning) despite the physical and psychological issues. Uncertainty is common at the state of diagnosis (what does it mean to live with this illness? How will it affect my everyday life?), start of new treatments (will it improve my state? Or worsen it? What are its side-effects? Risks?) and during transitions (will it progress? What does this new phase mean for my everyday life? ). Especially during moments of (apparent) danger (new symptoms, diagnostics, follow-ups, major interventions…) uncertainty can hit like a dagger – patients, loved ones and carers equally. Moments that are completely unfamiliar, complex and extreme.

Although Mishel’s uncertainty theory covers the patient’s uncertainty, in fact, the patient, carer, family and loved ones and also doctors, neighbours, friends… are part of it. Diagnosis, treatment and any other moments of uncertainty during the patient’s journey can affect his/her social and medical environment. Mishel’s theory can also be applied to nursing. It can be used as a guide on how to reduce patients’ uncertainty by providing information and communication and for better care in general like social support, circumvent loneliness, training in illness and uncertainty-related things, improvement in clinic environment etc.

In illness there are still two kinds of uncertainty: the existential one (a la Sartre and Kierkegaard*****) which everyone has to suffer from and the ‘clinical’(/illness related) one. The future is open and undetermined, but definitely holds more uncomfortable surprises in unpredictable illnesses. Sometimes it isn’t possible to provide a prognosis or treatment, sometimes the prognosis and/or diagnosis raises more questions than answers, sometimes illness turns life upside down, every day there is chaos and isolation.

Everyday life is controlled by symptoms, interventions, clinic and doctor visits, administration of meds,…a new routine and a new norm develop. However, the seemingly never ending cycles can be hit by further unpredictable emergency events, symptom development, new diagnoses etc. The illness itself gives sufficient space for (negative) feelings. No matter how strong the patient is, whether the symptoms themselves or their strong effect on every detail of the patient’s life, there will be moments where uncertainty puts the body and mind into darkness, hopelessness and frustration.

Our perception of uncertain events can either lead to hope and opportunity or danger and risk. Mishel realised that our cognitive abilities can alter these perceptions and reflections in a positive way, for example, via efficient self-organisation and coping strategies. Stimuli can trigger it in a negative way (symptoms, event familiarity and congruency). Structure providers can either increase or decrease uncertainty via social and educational support and nursing/clinic adaptation. Thus, patients and clinics should evaluate the best possible ways to brighten up the patient’s perception (e.g. improve communication, teach cognitive reframing strategies). Continuous uncertainty needs continuous adaptation. The unpredictable nature of illness comes naturally with the issue that former experience, skills or knowledge won’t help much. Illnesses are manifold, individual and complex, we can only live from one second to the next. Often we are thrown into a completely ‘new world’ and slowly learn what it all means and develop our own strategies to cope.

Just like Kierkegaard stated that objective facts are important, but our subjective relation towards them is far more important, truth is in the subjectivity. Our experience and our reaction matters. The interpretation of symptoms can alter the perceived uncertainty a lot. Depending on the patient’s past, possibly traumatic, events and symptoms each individual reacts differently to uncertain events in the future. The future is different from the past since we can choose. Those choices carry responsibility, again possible danger, but also hope. Possibilities that can make us dizzy. Especially in illness-related questions, ‘wrong’ decisions can lead to failed treatments, further uncertainty and burden. Obviously, the surgeries in 2017 were a huge mistake for me. We are now at a stage of palliative care where experimental therapy trials are recommended and no one knows whether it may bring some benefit of further damage. Nobody really wants to intervene or take responsibility (is passive non-action during extreme suffering also an action?). Patients, their carers and loved-ones carry a major burden, because those decisions can change and/or end life.

The illness is part of me, so the illness-related uncertainty is a personal one, might become an existential one. How can I find meaning in this absurd life?

As a patient I have developed several coping mechanisms to combat illness-related uncertainty. Whereas in the beginning I dove into medical research and read everything there is about my conditions, contacted doctors and researchers from all over the planet to find causes and therapy options; underwent countless interventions and hospital stays; I now know that acceptance is the best way to combat uncertainty. Meditation is a useful tool to ground and re-center. It helps me in being more mindful and aware of the certainty and safety I have and the positive effects uncertainty comes along. Firstly, I am grateful and cherish the definite support I will always have. The past is certain and until 2016 I had a wonderful life for which I am very thankful. The past years have taught me a lot and I appreciate every little moment, every little smile and act of kindness. Aside from the illness I live a life in safety, in a developed country with probably the best health care, without poverty or war, in freedom and without immediate catastrophes.

Secondly, uncertainty is linked with negative feelings such as anxiety, fear, stress and more and those feelings again catalyse any physical symptoms. Frequent meditation sessions can reduce this effect since it takes us back to the present moment, away from worries about our past or possible future. It embraces the present moment, we concentrate on our breathing and let go of any feelings, prejudices and the willingness to control everything. During meditation we breathe naturally, re-connect to our body and loosen our tight and stiff muscles and along with that our stiff set of mind. There is no ‘what if’, no complexity, no predictions or probabilities, just this certain, whole one moment. Outside there may be chaos and uncertainty, but we can always re-connect to our own body, re-balance our mind-body connection and be grateful for it. I am certain of my body and mind, so I cherish it. Find out more about acceptance and letting go here, here and here. Some guided meditation regarding this topic here, here and here. Related to uncertainty here and here. Meditation won’t solve your illness or any other problems, it won’t actually reduce uncertainty, but it can provide space for relief, rest, safety and calmness. It helps in the development of positive feelings (it literally helps with the release of serotonin and other ‘happy’ hormones). During my stay in a Buddhist monastery I also learnt how helpful walking meditation can be. In uncertain times we often don’t know where to go, we feel as if we are in midst of a vast chaos we cannot possibly understand, so walking simple geometric shapes like a line or a circle can soften these feelings. Focus on each step (because you can do so, whereas in our illness-related journey we cannot even see the next step, yet possibly the whole staircase!), focus on yourself and your environment. You are part of this world in which you can move, be grateful for it.

Another factor that reduces the negative feelings that arise from uncertainty is the connection and collaboration to others. Networking (e.g. group discussions in an outpatient pain management programme, online group chats in specific illness support groups…) between us patients help us to provide empathy and advice to each other. Both provide safety. We are not alone, we help each other. For the past years I have been in contact with many other patients and almost everybody agrees that this contact is not only helpful to share recommendations and experiences, but also helps psychologically. Nobody truly understands what we are going through unless we share some illness (including loved-ones and/or carer).

I love solving problems (that I can solve). My studies in maths and physics, later in theoretical physics, have helped me through the past years. It is the perfect combination of passion and distraction (under the condition that it is solvable). Whereas I cannot get rid of the inevitable uncertainty that comes with my illness, I can solve those problems, logic riddles and I can pursue what my heart beats for.

Look for something you love, something that distracts and can be understood and solved – it will provide a safe space. Similarly, find a place that provides safety and comfort for you (this might be a real location or somewhere in your mind). Every time you feel that the uncertainty starts to dominate you, you can escape to this place.

The origin of the fear of uncertainty is the fear of the unknown. Hence, often we equal uncertainty with the lack of information and look for more answers. Already Socrates knew ‘I know one thing, that I know nothing.’ Sometimes it is good to accept to know nothing, know less and stop researching.

The uncertainty principle of illness would go like this: delta way to go times delta resistance/non-acceptance. So simply let go of your resistance, accept the uncertainty around you and you will feel much calmer.

If we meet uncertainty with compassion (and self-compassion) the mysterious, potentially dangerous, uncertainty turns into something more humanlike.

Uncertain times like now won’t last forever (see impermanence). Since everything is only temporary, nothing can be predicted with certainty and nothing can be controlled fully. The wisest way is to let go of our willingness to control and know everything. ‘This too shall pass.’ is always a good phrase to repeat in situations of deep uncertainty, fear or pain. Don’t try to control every tiny detail in your life or worry about those parts that you simply can’t control, but rather choose to rest in uncertainty. As Feynman knew:

I think it’s much more interesting to live not knowing than to have answers which might be wrong. I have approximate answers and possible beliefs and different degrees of uncertainty about different things, but I am not absolutely sure of anything and there are many things I don’t know anything about, such as whether it means anything to ask why we’re here. I don’t have to know the answer. I don’t feel frightened not knowing things, by being lost in a mysterious universe without any purpose, which is the way it really is as far as I can tell.

There is no absolute certainty and this is beautiful. Curiosity is one of the major driving forces of humanity. Quantum mechanics, science, our bodies, the Earth, the universe(s) are complex and our (present) perception and knowledge is inevitably limited. This is again beautiful.

Absurdly, more certainty about an illness (better predictions) doesn’t necessarily lead to a better understanding or feeling. It may decrease our hope and willingness to fight. If I always knew the outcome of new treatment options would I try them, would I continue to fight? Fight for nothing? No change at all?

We are all individuals and every little choice and factor around us can alter predictions – a 12-months survival prediction can turn into a decade and a simple standard intervention may kill a patient. Thus, sometimes it is better to take a step back from it. Accept the uncertainty and rather put your energy into something else.

Reaching out with your fears, problems and advice to other patients suffering from similar illness (peer support, support groups e.g. of people suffering from chronic pain, intestinal issues, rare illnesses, your illness etc) can be valuable for yourself and other patients – but be careful, everybody is different and has different reactions to therapies or developments. In uncertain situations various feelings arise and most often it is best to talk with your loved ones, family and friends. They know you – as a person and not only as a patient. Lastly, it can be helpful to see professional help e.g. from psychologists, counsellors, somebody who has an objective view, listens and can give advice on coping mechanisms. It is completely understandable to feel lost and alone, afraid of the illness itself, the uncertainty and suffering, afraid of the future or traumatised from the past. Be honest to yourself and seek help.

From my own experience I also recommend being honest about the issue of illness-related uncertainty in your life to your social, work and/or study environment. You might need a more flexible schedule and deadlines due to unpredictable symptoms or the necessity of interventions and longer and unforeseen breaks. There are also other work/study adaptations and accommodations that may decrease uncertainty or uncertainty-related issues, for example, a suitable work space where you can lay down when needed, have your own intimate space or a bathroom nearby.

If we face uncertainty as danger this only leads to anxiety, emotional distress, frustration and more which then again can amplify symptoms. Hence, take your time to find some ways of support or adaptations.

Some encouragement now.

I used to love the unknown, taking risks during my runs and going on explorations in the forests and through London. This has changed now, uncertainty has scared me in the past years. Most of my life went pretty well until 2016. I knew what I wanted, I had a plan and it all worked out pretty well. Everything was under my control. Then, peng, the illness hit me pretty hard and the feeling of uncertainty (at least of that kind) was completely unfamiliar. Throughout the past years, my illness has progressed and the uncertainty has increased along, but so has my acceptance.

Nowadays suffering and uncertainty are inevitable and very present. Clarity arises when we have gone through uncertainty and not before, simply from demanding it.

But what if danger becomes opportunity and opportunity becomes danger? This is a very narrow path in illness, especially in conditions that are unpredictable, rare and complex, illnesses without long term prognosis due to the lack of studies and comparisons and/or illness with various possible outcomes.

Mishel emphasises the importance of the interpretation of uncertainty based on illusion and interference i.e. again via cause and effect. Obviously, there is a longing for a certain outcome in any situation. For me, it is simply some kind of improvement of life quality, some kind of health stabilisation and a bit less suffering.

She later improved her framework (see her sketch: self-organisation, probabilistic thinking and new life perspective) and included the fact that the patients can grow along/with/due the uncertainty (in)to a new system. I constantly live with this uncertainty and this consciously and unconsciously changes the effect of uncertainty on my life.

How we cope with the illness, our daily mindset etc does have an effect on our symptoms and sometimes this can make a big difference – especially when we are right on the edge.

In my opinion, Mishel wants to show that uncertainty should be seen as a neutral phenomenon which becomes something good or bad due to our interaction with it. This is where we meet Rovelli and Barry again. It gives me a lot of hope. It gives a reason to fight.

[Explanations:

Cognitive capacities: patient’s subjective interpretation of illness, beliefs, knowledge, skills…

Antecedents of uncertainty = stimuli frame (symptom pattern, event familiarity, event congruence) + cognitive capacities + structure providers (educational, social support, clinic authority)

Appraisal of uncertainty = inference or illusion → danger or opportunity

Coping with uncertainty = coping strategies → adaptation

Note, in the reconceptualized theory Mishel added:

- Self-organisation

- Probabilistic thinking

as capacities and the

- Formation and development of a new life perspective/path]

We have to develop adaptations and face uncertainty as much as it is possible for us. Just like a cactus. They have a remarkable ability to survive in the driest deserts due to their adaptations, both in anatomy and life strategy.

We cannot reduce the uncertainty in today’s life, but we can increase our acceptance and cope with it.

Top tips to face uncertainty:

- Don’t avoid it. Reach your destination without GPS, wake up without an alarm, visit a restaurant without having a look at the menu before, choose another way to work, go on a trip without booking anything and without having a look at the weather forecast.

- Focus on what you can create on your own. Here you can often predict and/or control the next step. Be creative. Bake (that’s what I do).

- Appreciate uncertainty. Life would be very boring without it. Embrace uncertainty.

- Ask yourself: Why am I afraid? Even the most difficult and hopeless situations have some safety left.

- Exercise mindfulness. Meditate. Be aware without any judgement or evaluation.

- Pursue a task that gives you a constant in your life. Build up routines where possible.

- In case of acute ‘panic’ situations: Develop your own coping mechanisms. This could be something personal, some meditation techniques or breathing exercises.

- Reframe your situation. From another perspective things might look completely different. Have a look at cognitive reframing below.

- Recall that you are safe. Go to your safe place. (Hug your loved ones, your dog…) Cherish the safety that is left.

- Talk about your fears. Whether it is with a friend, loved one, carer, counsellor…or yourself, your dog. Speak out your fear aloud. Seek for help when needed.

- Do something, don’t get lost in catastrophising. Take action. Also, don’t get lost in the sea of possibilities.

- Develop new ways or skills to combat the situation.

- Accept what you can’t control. Appreciate what you can control.

- Trust. There will be better times. There will be guides to follow.

To cope with (existential) uncertainty one can choose faith, science or a combination. There is no perfect knowledge and blind faith won’t lead anywhere in my opinion. Take one thing at a time. Often there is no other way and it will simplify things a lot.

In illness we can research, collect and analyse data, improve therapy strategies, diagnostic processes etc. At the same time faith or hope for improvement, faith in our own body and environment (both, medical and social) is a helpful companion.

Cognitive reframing is a psychological tool where feelings and situations are identified, reflected and viewed from another perspective. Again it is our observation and interaction with the emotion or event that makes it a subjective experience and different perspectives lead to different outcomes. A positive mindset can move mountains, a negative mood can prevent possible positive progress. Try to identify faulty thoughts and triggers and change them. Otherwise you will be stuck in the same cycle.******

A simple exercise is as follows: Write down what you think. Next, add facts that support this thought. Then, add past experiences, deep feelings, beliefs etc that accompany this thought. Finally, evaluate whether this thought is real and rational or just some artefact. You can also evaluate your thoughts related to a certain event. Identify the dysfunctional ones (that hinder progress, magnify the negative side, …) and try to find functional thoughts instead. Mindfulness meditation is a suitable tool to increase awareness for your thoughts and internal beliefs.

Uncertainty can be as big as our imagination. Hence, stick to the given facts and limit the information intake (at least in some situations). I am very poor at this myself. The more I research, the more questions there are and the negative effects related to uncertainty only grow.

Obviously, there is a big difference between the uncertainty of life and the uncertainty of illness. The former may contain a bit more beauty. However, illness can also be embraced and one can flourish (into) something one would never have anticipated, against all odds…

Uncertainty also means possibility. Sometimes this means to risk something, sometimes this means to wait for something to happen.

Our brain always tries to predict what happens next. We love to plan: our meal (unless you are tube-fed), our day, our holidays, the next week, month, year…the whole life. But illness can disrupt every part of it quite a bit due to the lack of predictability and control. Moreover, there are types of uncertainty we can (happily) step into, but illness most often throws the patient into a new uncertain state that cannot easily be faced and/or changed.

Uncertainty has helped us to survive, unknowns are potential threats and should be avoided. But only the risks in life give us new opportunities, the possibilities of making decisions and finally improvement. Nonetheless, a healthy amount of uncertainty would be appreciated.

One also has to differ between known unknowns and unknown unknowns. Empirical research shows that people react differently to probabilities that are known in contrast to those that are unknown (i.e. where discrete probabilities cannot be assigned).

A short overview:

Known knowns: things we know we know i.e. we are aware of and understand. E.g. I suffer from intestinal pseudo-obstruction, a very difficult to manage condition.

Known unknowns: we know that there are things we don’t know i.e. we are aware of it, but don’t understand it (aka uncertainty type 1 or Socrates knowledge or ‘conscious ignorance’).

Unknown unknowns: things we don’t know we don’t know i.e. we aren’t aware of them and (wouldn’t) understand them (aka uncertainty type 2 or ‘meta ignorance’ ), mysteries yet to be known e.g. something we don’t know (yet)…

For completion, unknown knowns: known in some sense, but then practically unknown e.g. forgotten, ignored i.e. we are not aware of them (consciously or unconsciously) but (would) understand them e.g. I know that I am disabled, but in my daydreams I ignore it and sometimes overdo it.

Where ignorance can be a bliss, sometimes it is good to be unaware of certain knowledge and sometimes it is also good to not understand or know unknowns.

The weight of uncertainty is associated with its probability (if it can be given) and so is the effect uncertainty has on us. Unknown unknowns with missing/unaware information is not as frightening as known unknowns (I guess it is hope that arises in the first case). Thus, I think it is better to let go of the willingness to know the missing information in illness.

Song recommendations to embrace uncertainty:

- Here Comes the Sun, The Beatles

- I Will Follow you Into the Dark, Death Cab for Cutie

- The Wall, Pink Floyd (whole album)

- The Future, Leonard Cohen (whole album)

- Scare Away The Dark, Passenger

- Bridge Over Troubled Waters & Hazy Shade of Winter, Simon & Garfunkel

- I Won’t Give Up, Jason Mraz

- I Know But I Don’t Know, Blondie

- Be Good (Lion’s Song), Gregory Porter

- Want, Birdtalker

- What’s happening?!?!, The Byrds

- Restoration Song (Hold On), Song of Cloud

- Ooh Child, MILCK

- Can’t Be Sure, The Sundays

- The Bird, Anderson. Paak

- Song of Good Hope, Glen Hansard

- Hanging on a String, Loose Ends

- Somewhere Over the Rainbow, Emile Pandolfi

Back to Nagarjuna.

The key lessons together with some more science, Greek and Eastern philosophy in the book Helgoland is the importance of interactions. To repeat, for Nagarjuna, emptiness is the absence of independent existence, the absence of independent identity. I exist because of and in relation to something else. There is no autonomy. There is no ultimate reality.

As much as we might lose control and certainty since we are dependent on anything else, doesn’t this give a feeling of security, warmth, hope and deep comfort? We are all part of the same net, we are all floating through the same foam. For me, it liberates me from attachment. We can let go. But can we also let go from (our own individual) suffering?

It also fills me with gratitude and amazement. We are all empty entities. But in and due to relation(s) we become something. I am the collection of interdependent phenomena and so are you. Nothing exists in itself, everything is only here through the (inter)dependence with everything else (I have to repeat it).

Same is true for quanta that we can only evaluate in interdependence in Rovelli’s relational QM, if you want to know more about the physics side, have a look at this publication plus refs.

Humans or things are nothing without their interactions between each other. Interpreting life with this as underlying view differs from the standard analysis that isolates, identifies, defines objects away from each other. There is no intrinsic reality (where uncertainty is naturally a part of). This has a very calming effect. It gives me a sense of safety. The bigger picture is what matters. When uncertainty frightens you, zoom out and keep calm.

This can also be found in this poem by the the Nobel Prize winner of literature in 2023, Jon Fosse.

Everything we aim for, everything we have made, created, reached or developed is only due to all those relations, the web of exchange, the flow of communication, cooperation and connections.

Moreover, there is no outside from which we could ever observe, we are embedded deep down in the foam.

Barry argues with two examples (Double slit experiment and Schrödinger’s cat) how important observer dependence is. Observer dependence arises from our interaction with the experiment (it is the disturbance of an observed system due to observation that changes the system). This can be applied to uncertainty and any kind of negative experience. The more we observe/ the deeper we experiment with or analyse the situation, the higher the interaction and, thus, the effect on the whole system (including us).

Uncertainty might be THE problem of our time. Of all time…it is the lack of knowledge that motivates us – to research, to search for answers, to live, to hope…

It is unavoidable, on the subatomic level (HUP…) it is as fundamental as on large scales (e.g. chaotic behaviour, stochastic dynamics) and why should human scales be free from it?

Without uncertainty, one would never be happily surprised by a light summer rain on a forecasted hot sunny day, the win of your beloved football club against the best team in the world, meeting a soulmate on the tube or finding phenomena such as radioactivity. Crime novels are only interesting when we don’t know the end yet. And the complexity of systems, whether it is the weather, our body, fauna, flora or life is beautiful, no matter how many questions or issues it causes.

Uncertainty gives us freedom and the responsibility of life. It is the space of all possible evolutions, the space of all decisions and choices. Uncertain times are often those of new choices and important decisions, where freedom is embraced and major changes happen. Uncertainty gives us hope, realistic hope. Hope for improvement, new ways and possibilities and more (unknown unknowns?). And hope gives us strength and endurance. And in the end, uncertainty is/becomes knowledge.

Uncertainty proves that nothing can be taken for granted, it grows gratitude and awareness. Without uncertainty humanity wouldn’t have come so far.

Uncertainty is essential.

Non-accepting (the uncertainty) is suffering.

We need patience for that. I am patient and things will develop along. I do my best in accepting the unknown and unknowable future, learning from my past and changing the present moment where I can. I let things and I let myself develop, I let nature be and I let go of control.

Habe Geduld

gegen alles Ungelöste in deinem

Herzen

und versuche,

die Fragen selbst liebzuhaben,

wie verschlossene Stuben und wie

Bücher,

die in einer sehr fremden Sprache

geschrieben sind.

Forsche jetzt nicht nach den

Antworten,

die dir nicht gegeben werden können,

weil du sie nicht leben könntest.

Und es handelt sich darum:

alles zu leben.

Lebe jetzt die Fragen!

Vielleicht lebst du dann allmählich,

ohne es zu merken,

eines fernen Tages

in die Antwort hinein.

‘Be patient toward all that is unsolved in your heart and try to love the questions themselves, like locked rooms and like books that are now written in a very foreign tongue. Do not now seek the answers, which cannot be given you because you would not be able to live them. And the point is, to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps you will then gradually, without noticing it, live along some distant day into the answer.’ from Rainer Maria Rilke’s******* 'Letters to a Young Poet' which I can recommend in general (letters to his buddy poet Kaddus about uncertainty, intuition etc).

Follow Rilke’s advice. Love the questions, love uncertainty.

Don’t avoid the major questions. Don’t avoid questions that might lead to uncomfortable, uncertain or no answers. Life needs questioning and wondering. Similarly, don’t force answers. Let go. Go with the flow. Dive down into yourself and life will unfold the right path for you. The answers are in the questions. The questions you ask yourself have some (deeper) meaning which sometimes is even more important than the answer itself.

Let everything happen to you: beauty and terror. Just keep going. No feeling is final.

from the poem ‘Go to the Limits of Your Longing’, listen here.

Even if you don’t believe in God, you can trust in the natural development of life. Accept how life unfolds. Uncertain and difficult times won’t last forever, suffering will pass.

What are your limits of longing?

Let it be your energy

Embrace the moment

Make decisions

Decisions that change your life

Play along

Of tomorrow’s unknown

Tune endless parameters

Turn worry into wonder

And progress

Love the questions

Embrace the unknown

Turn it into

creativity

knowledge

curiosity

And hope.

Willingness to accept.

Be brave. Be human.

More thoughts in between here.

References:

- Mishel, M.H. (1981). The measurement of uncertainty in illness. Nursing Research, 30, 258–263.

- Mishel, M.H. (1988). Uncertainty in illness. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 20, 225–232.

‘We demand rigidly defined areas of doubt and uncertainty!’

Douglas Adams, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy

Summer 2016

All About Therapy Part 1

Some serious topics to follow. I would like to write about the care of patients with (severe) chronic illness, especially when caregivers are close people such as family members or partners. When a loved one becomes a caregiver, the relationship inevitably changes. There are two levels: family/ loved ones and patient-carer. Obviously they mix as things unfold.

A long-term illness changes the life of the patient and the life of his family. In most cases, patients are dependent on continuous and manifold support from these persons. Whether it is the daily support from the household, mobilising, transport and medical needs or psychological help during times of flare ups, pain, difficult symptoms, during times of uncertainty, fear and anxiety or support during rather intimate needs (giving enemas, washing, cleaning vomit or faeces, catheterising etc) and dangerous emergency situations (calling the ambulance, providing first aid, waiting during day-long surgeries, ‘holding hands’ in life-threatening situations…).

However, who is the one that cares about the needs of the caregivers who equally suffer from the uncertainty, worries about their loved ones and their responsibility as caregiver? They might not have the physical suffering, but they observe a loved one in pain all day and often they simply cannot help much.

Family members have to adjust their expectations in daily life, holidays, career, social life etc. Isolation, reduced quality of life, lack of privacy and negative feelings such as guilt, anger, sadness and grief lead to major challenges. Caregivers suffer from mental (depression, anxiety,…) and physical health concerns (sleep problems, fatigue, even further illness, burnout,..) as well as secondary issues such as work (reductions of hours, loss of work place,…), social (relationship problems, no time for friends and social activities,…) and financial challenges.

One always has to plan and organise and in the end these plans don’t work out and often they have to be cancelled. A deeper and empathic understanding is necessary and will necessarily develop. Nonetheless, there will be times where this understanding and empathy will be challenged. The energy for arguments is low, but disagreements will build up inside the patient and caregiver.

Caregivers carry a huge responsibility, a responsibility that can put a major burden on caregivers, patients and their relationship. Their duties and roles vary from providing basic needs (transport, food prep, shopping,…) over medical tasks (administration of meds, medical treatments, symptom management, monitoring…) to emotional and social support. They function as coordinators of medical treatments and doctor appointments and might support decision-makings or even have to make important/life-changing decisions.

From my own experience I can say that my mum never rests. Her thoughts are always with me. She knows that things can happen at any time, she sees in how much pain I am, she has been with me during and through countless life-threatening and dramatic situations, she has been with me during times I wasn’t able to do anything and communicate on my own and during times I was about to give up. She holds my hand, encourages me, supports me throughout…but who is the one who looks after her? Encourages and supports her during all these times?

Caregivers have to accept their own limits. My mum lives for me only. But one should set a limit, ideally have a life outside those worries – which realistically, isn’t possible.

Carers have to care for themselves – who are the ‘carers’ for the carers?

Self-care is as important as patient care. Carers should not stop following their own goals.

A system of several people supporting each other (friends, neighbours) and understanding the situation may be a good tool. Patient and caregiver shouldn’t isolate and let other people know about the situation. Again, from my own experience I know how difficult it is to open up about the difficult situation. Often we don’t want to ask for help or people ‘outside’ our bubble simply cannot fully understand what’s going on. This lack of understanding can hurt a lot and often leads to further misinformation. Nonetheless, be honest, ask for help – whether it is friends, neighbours or professional bodies. Nobody can manage such a life on their own. Moreover, one always needs some kind of emergency plan in case the caregiver cannot fulfil his/her tasks.

In Germany, everybody who has a long-term condition can be classified into a system of different levels of disability and need of care (GdB ‘degree of disability’ and Pflegegrad – ‘degree of care’). The GdB indicates how much the functional impairment(s) affect the body, mind and work/study/social life, the general ability of participation in life and ranges from 20 to 100 (%) (above 50 you are severely disabled – ‘schwerbehindert’). The Pflegegrad is classified by the need for care due to functional impairment because of the health issues.********

Along with these, the patient and caregiver receive certain beneficiaries, for example, money, auxiliary devices, etc., but also advice from professional counsellors on how to improve care at home. My caregiver is my mum, other families prefer to arrange nurses from outside. We have decided for the former as I need help throughout the day and things are pretty unpredictable and nurses come during certain times each day only. We also have support from an outpatient care service for everything regarding TPN, morphine pump and my Hickman line (they have taught us to prepare my nutrition bags and the dressing change of the Hickman line, handle the Hickman line, visit us when needed and every few weeks to see whether everything is ok, for BIA measurements etc) as well as an ostomy nurse if needed. Nursing qualities also involve monitoring e.g. blood pressure (e.g. in cardiovascular issues), glucose levels (e.g. in diabetes); applying meds (injections, subcutaneous, iv,.., administration in Alzheimer patients), dressing changes, changing positions in patients that are bed-bound etc… Some of them are life-important. In palliative care often this also includes the handling of feeding and drainage tubes, catheters and tracheostomies.

Further, for example, I have a care bed that can be adjusted to my needs (e.g. legs up during blood pressure drops, head up during vomiting), a shower chair (POTS, orthostatic intolerance, dysautonomia can also affect the ability of standing longer, especially under temperature changes) and a wheelchair for longer walking periods or bad days/long outpatient clinic stays. As a chronic illness patient I am on many meds, some of these are very expensive, I am on TPN and I have an ileostomy, I have to catheterise and flush my ileostomy etc (and all of these come with accessories again e.g. additives, syringes, sterile tissues etc) … We would never be able to pay for everything without social benefit.

It helps at work/study (for example, with a GdB above 50 there is a certain protection against dismissal, shorter working hours, more holidays etc) and social life.

Having a GdB also provides beneficiaries such as free transport (public or taxi rides depending on the severity) and reductions in ticket prices.

Along with the percentage there are certain markers (Merkzeichen) that indicate severe walking and/or standing disability ‘G’, need for a caregiver at all times ‘B’ and much more which all are very helpful in daily life. They all come with support accordingly such as the availability of parking spaces near clinics, free rides, and so on. And obviously, one can always show/prove one’s disability – unfortunately, often people don’t necessarily believe it otherwise.

I definitely recommend making such applications. It is some paperwork and they will also need lots of evidence, but it is definitely worth it. Moreover, both GdB and Pflegegrad change according to the patient’s disability i.e. when the illness progresses, a new application might be useful.

More information (for Germany) you will find at the care administration (‘zuständiges Versorgungsamt’) where special experts evaluate your situation according to certain rules (‘versorgungsmedizinischen Grundsätze’). You will need medical evidence such as hospital letters, letters from your GP/other departments, the doctor who treats the condition that makes you disabled, letters from rehabilitation centres, care assessment reports, etc.

All in all, there is a broad range of support possibilities for the patient, caregiver and the whole family: support in their household, medical care, general care and engagement, basic care, transport etc as well as financial help.

Moreover, there are support groups, care courses and care consultations that provide information and share practical knowledge to improve care at home. Also, if you aren’t happy with their decision and think you are entitled to have a higher GdB you can file an objection and ask for a re-evaluation.

Further resources can be found here (in German):

- Pflegegrad

- all about care

- GdB

- laws

- your insurance

Similarly, for the UK

I am certain that other countries provide similar authorities and support. In the UK, you have to ask the local council’ social services to arrange a health and social care assessment. There is financial help as well as social services, nurses and medical trained persons or paid carers that support you at home and improve your environment (equipment, gadgets, personal security systems). During my studies in London I learnt that there are many differences between the German and British health care system. One of them is that the UK offers many interventions and diagnostics as outpatient appointments.*********

Thus, the organisation of transport is very important – which was indeed quite good during my time over there. There is a state benefit for carers each week and depending on their income, carers can ask for further financial help. I do hope that there will be a European/International disability card one day. Obviously, having a chronic condition doesn’t really allow one to go on frequent holidays, but it would be of great help if there were international guidelines and benefits for disabled people (especially, when treatment outside the country is necessary).

Professional help for patients, caregivers and further family members can be provided by social services, psychologists, social counsellors and certain institutes (in Germany, for example, MZEBs – centres for complex illnesses, disabilities for adults, that specifically evaluate the situation with the aim of no over- or undertherapy – next post!). Your insurance might be able to provide further advice. As part of having a Pflegegrad one is also entitled to receive recommendations to whom else to turn to.

Aside. Uncertainty theory (see above) can be used to provide better caregiving, for example, via more communication and information sharing such that patients, carers and family understand illness and interventions. A safer and more comfortable environment may improve certainty. Further, ‘minor’ applications/coping mechanisms and mental training (cognitive reframing tools, communication and problem solving skills,…) can be taught to raise autonomy and self-control.

Most importantly, the access to medical knowledge of one’s conditions should be easily available and understandable. There shouldn’t be any confusion about the therapy or the reasons for choosing certain options – this would only increase the inevitable uncertainty that comes along with new therapy trials.

Mishel’s works provide tools and principles for the selection of treatment options/interventions that would have a positive effect on psychological issues of uncertainty.

Caregivers should take care about their state of mind (same for the patients). Both, the physical and mental strength can grow beyond human limits. Often they cannot change the situation which is cruel for themselves since they want to change something and often this is again a burden for the patient/loved one which results in a lack of transparency and honesty. Thus, having some space for thoughts and feelings apart from each other may be of help. Always remember that as a carer you have to be as healthy as possible, hence, overburden should be avoided at all cost. (Are you overwhelmed as a caregiver? US questionnaire here).

Embrace caregiving. You will learn new qualities and skills, learn new aspects of life.

Relationships will be questioned, but the patient and caregiver will grow closer. Carer and patient/loved ones spend more time together, get to know each other better – in all possible ways. When we start talking about our pain, our fears and suffering, our shared uncertainty and important life decisions, we open up and show our innest emotions. We get to know each other during the darkest times, during days without hope and enormous pain. On one side there is the patient’s fragility, on the other the carer’s responsibility. The patient is severely dependent on the carer and so will the carer put all his/her energy into the caring. This dependence can become dangerous, especially, when there is only one carer and patient in a bubble with no further help. Being dependent on a carer in most parts of his/her life, can be very difficult for the patient. It can come along with a sense of guilt, shame and/or grief. Patients may feel like a burden, get anxiety when alone, feel useless compared to the carer, … Young people often struggle with their impairment, because they cannot have a normal life as their peers have. Again, patients should be honest about their feelings and share them with someone (ideally the carer).

Illness may not only decrease the quality of life of the patient, but also the family members’, life is turned upside down and normality doesn’t exist anymore. But on the other hand, there is more communication, common understanding and listening quality will increase (not only about the illness, but about the views and opinions on life in general). It opens up completely new spheres, there are topics one would never have talked about.

The illness will take time that would have been for other (important) things. My mum basically doesn’t have any spare time between me, illness-related stuff, Bo and her work. This shouldn’t be the case!

But she can be sure that her loved one is in good hands. I think that this is one of the most important benefits for family members as carers: they are the one’s under control and can be sure that their loved ones get all the support they need. This comes along with a feeling of satisfaction.

Moreover, the patient benefits from the social/mental support, because the caregiver knows the patient as a person without any illness. A hug or holding hands can help sometimes more than any medical application.

Caring does not only strengthen the empathy and relationship to the patient/loved one, but also to others. Moreover, the carer gains medical knowledge (my mum could work as a nurse, if not even as a doctor by now).

Carers will be more grateful for life despite the troubles, fears and uncertainty.

Teamwork is key. My mum and I know how to split tasks. As long as I am still able to, I manage those I can do such as taking/applying my meds, preparing my nutrition and infusions, ostomy and catheterisation, managing doctor appointments and clinic stays. Sometimes my conditions are sufficient to keep me occupied, so I am very grateful that my mum takes over most of the organisational stuff (frequent phone calls, paper works, shorter transports, picking up meds and recipes etc).

Our restriction of social contact is not voluntary, but due to the lack of energy and time. Throughout the past years my mum has supported me each and every day, our bond has grown stronger and stronger.

Caregiving as a family member is much more complex and difficult as one probably imagines, and most often there is no adequate training and preparation. Every caregiving is different, because every patient is different and every person (as a family member) is different. The illness as well as the duration, intensity, qualities of caring and along with that the severity of responsibility will change over time and caregiving has to adapt accordingly.

In my opinion, there should be more awareness about this whole topic. Especially regarding the ageing population nowadays – caregiving is a growing subject.

All loved ones/family take some sort and part of caregiving, just by definition – but there is a difference to taking over official care. The carer has the official responsibility to administer official medical tasks and should undergo certain medical training, often he/she gets paid (see before, Pflegegrad). Every family should carefully decide whether to take over care of themselves or ask for outside help.

What qualities should a caregiver have?

- Learn as much about the illness(es) and history of the patient.

- Know about his/her daily needs including all meds, medical interventions and learn how to administer them. First aid skills are vital, too.

- Know how to monitor and evaluate vitals and understand when to call for an emergency. Good judgement is vital.

- Know when to ask for medical help. Follow the advice of medical experts. Collaborate with the doctors (don’t take over charge).

- Get to know the patient (if you are coming from outside), everyone is an individual and needs individual support.

- Empathy.

- Listening and communication qualities. Work as a team with the patient (family and doctors).

- Organisational and logistical skills.

- Be flexible.

- Patience.

- Confidentiality (especially when you come from outside). Don’t share anything outside.

- Balance care for your patient(/loved one) and yourself. Set boundaries. Care about your health.

- Reach out when needed. Ask friends, family and/or professional bodies for help as needed. Accept help.

- Passion. Embrace caregiving.

The stress, fear, constant hard work and concentration as well as lack of prognosis and hope can lead to a carer burnout, especially when the carer is some family member. They may feel exhausted, overwhelmed, trapped, guilty, lost and alone. Financial issues, lack of progress or illness progression and social isolation all add up to it. Carers should seek (professional) help, especially when they feel depressed.

Often, the carer cannot be as open as he/she would like to be in front of the patient. Despite my illness, my mum and I do argue (which is completely normal). Depending on my state I can be very upset myself and may say something inappropriate to my mum I don’t necessarily mean in that way. How should my mum react towards this? The symptoms, meds, my situation – they can all drive me mad. Often, carers are in such dilemma situations.

My mum is always with me, when not physically, her thoughts are revolving about me and whether I am as safe as I can be. I admire her so much for her compassion, empathy, loving-kindness and her strength. My illness can be pretty unpredictable, a ‘Something is weird’ in the evening can turn into an emergency call at night following some surgery or a whole night wide awake on the bathroom floor, driving to some holiday apartment can turn into a helicopter flight to a foreign clinic because of a small intestine ileus. She has a 24h job as a carer and mum. Nobody can carry this weight for so many years.

The closer bonding in patient-carer/loved ones can be an advantage, but it can also turn into a difficulty for the carer whose compassion and mental health simply cannot face the cruelty under which his/her loved one lives.

Families and patients often undergo traumas such as certain surgeries, times of severe uncertainty, poor outcomes of therapies, near-death experiences, bad doctor/clinic experiences etc which need treatment accordingly (another problem is the development of PTSD associated with the illness). However, often the aftermaths on the carers and family members aren’t sufficiently treated. It is crucial to minimise stress and further negative emotions. Caregiver stress syndrome and burnout are real terms and should be avoided at all cost – both, for the carers and patients.

How to deal with stress as a carer?

- Get further help. Friends, further family, neighbours or professional help. (E.g. for shopping, household, transport,…, psychological help!,…)

- Don’t fully isolate yourself. Talk to your friends and take part in social activities /if possible).

- Talk with your workplace to adjust working hours, a more flexible schedule etc.

- Find some way to relax (e.g. meditation, sports) – save those hours for yourself only.

- Look after your own health.

- As a family member/loved one try to set a border between your task as a carer and your emotional feelings. ‘Don’t take it too close’.

- Take breaks. Time for yourself only.

- Don’t withdraw from your daily activities. Don’t neglect yourself, your body or mind.

- Recall why you decided to be a carer. Look for that (com)passion again.

- Don’t tell yourself that you are the reason for the medical problems. Most often you simply cannot change anything. Don’t feel incompetent. Ask for medical help when needed.

- Be informed about your tasks to reduce as much uncertainty as possible.

- Accept help. In your situation this is completely ok. Be honest about the situation.

I will post an interview with my mum next time, to picture the view of a caregiver mum.

Part 2 will be about palliative care as well as over – and undertherapy. Along with that I will talk about the importance of patient-doctor communication.

Song recommendations

Sufjan Stevens & Angelo De Augustine: Reach Out

The song starts with a reference to the German movie ‘Der Himmel über Berlin’ (‘The Wings of Berlin’) from 1987 by Wim Wenders. Two angels observe people on Earth and all they can do is provide courage from afar.

One of them decides to become mortal, pursued by the desire to sense and love. He wants to take part in the cosmic dance. When he falls in love with a circus artist (isn’t she somehow a connection between the grounded Earth and Sky above) he departs to Earth. It is a movie about the power of love, it overcomes barriers and worlds. Interestingly, it starts with a black and white screen and when the angel comes down to Earth the world becomes colourful, it isn’t all happy, but that’s how reality is. There is also a lot of German poetry mentioned and invites us to dream and wonder.

I am not religious, I don’t believe in angels. I mean angels per se that are somewhere in the sky and help God out. But our remembrances of loved ones, the words we leave on Earth, the thoughts we spend on humanity, friends and family or strangers, the empathy and compassion, the hope and forward thinking we spread, the love we give and receive, the trust we build on…aren’t they the angels that help us to combat any difficulties and the absurdity of life? It is about isolation and life.

Anyway, taken from this movie you listen to ‘I would rather be the flower than the ocean’ in the beginning of the song (along with a video of two dogs that are angel-like, pure and innocent). It talks about mortality and the stability Earth provides. The beauty of mortality is its realisation, it connects us even more, to those that passed and those that live.

For me, chronic illness feels like losing the flowering scent, one petal after the other, the last petal, the stem and finally the roots.

Now, the lyrics start with

‘I have a memory (very Sufjan-like)

Of a time and place where history reside’

That’s the place to go in difficult situations. What do we learn from the past? How do our experiences lead us? Who guides us?

‘Reach out, reach out and all at once the pain restores you’

See and feel the connections of past and present, between all beings and experiences … and the path will unfold. Together we will reach our goals. Beautiful pain will arise. This pain will make us grow.

‘I have a memory of a time and place where history resigned

Now in my reverie

For the guiding light that opened up my mind’

The song talks about the importance of relationships (see above, Buddhism and Rovelli’s perspective) and finding the inner self through our interactions.

Fitting to this,

Simon & Garfunkel: El Condor Pasa

‘I'd rather feel the earth beneath my feet’

Safety, certainty, grounding, connection, that’s what we are looking for. Being in control of your life… I like to be the flower rather than the ocean. And, similarly, we want to become free and do not want to be attached to something, spread our wings and fly over the oceans and forests just like the condor (a bird in the Andes).

We want to live our life – very simple.

And finally Daydreamer by Roo Panes.

‘Do you wonder where you'd be if you'd ever dared a daydream?’

Not too much, but not too less. Allows us to wander wherever we want. Fly away, somewhere, and breathe. Dance through your daydreams. Let go. Wonder where, wonder what, wonder. Hope will come. Step back. Don’t take life for granted.

Some things start with a daydream. Wander through your (deepest) thoughts and wishes. Just don’t get lost.

More songs, for daydreaming during cold days in Winter:

- Sunlight, Rhodes

- Clouds, Pano

- Imagine, John Lennon

- Summer Rain, Zimmer90

- The Summer Isles, Roo Panes

- Day Dreaming, Aretha Franklin

- Astral Weeks, Van Morrison

- A Rainha, C. Kilgannon & A. Lunardelli

- Daydreaming, Massive Attack

- Tide, The Antlers

- The Equator, Tortoise (whole album TNT)

- I don’t want to go that way, The Paper Kites

- Far Away Island, Blur

- Twin Parallel, Rogue Valley

- Strawberry Fields Forever, The Beatles

- Reflexion, Sufjan Stevens

- Walking Backwards, Ben Howard

* Barry is the founder of the Human Values Institute which ‘educates people about essential inner human values in a non-religious context’. I like their concept that ‘from honesty and respect, trust naturally develops’. He also founded the altruism in medicine institute which promotes that compassion and mindfulness is equally important in healthcare as medical competence.

** In Helgoland Rovelli debates that the Middle Way and the framework of emptiness can be found in physical reality, too. Reality is made up of relations/interactions only. I also recommend his recent ‘White Holes’, ‘The Order of Time’ and ‘Reality Is Not What It Seams’ (they can be understood without having studied physics) and ‘Quantum Gravity’ (for theoretical physicists).

*** Basically the article is about the energy levels of a 1d anharmonic oscillator using transition amplitudes (for quantum jumps of electron orbits) and also includes the first notion of the Heisenberg commutator. It lays the basis for the formulation of quantum mechanics with matrices where the particle’s properties are given as matrices that evolve in time. During his wild climbs on Helgoland he realised that the non-commutativity of observables might solve the issue of the calculation of spectral lines of hydrogen. Again it is the relation between the observables that should make the framework for Heisenberg’s quantum mechanics.

**** For the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale (which turns out to correlate with the level of stress coping) the following statements are rated:

- Unforeseen events upset me greatly

- It frustrates me not having all the information I need

- I should be able to organise everything in advance

- When it’s time to act, uncertainty paralyses me

- The smallest doubt can stop me from acting

and analysed. It is a test that helps in the evaluation of somebody’s reactions, opinions and beliefs in regard to uncertain events.

***** which is: we are unable to reach full certainty attached to logical or mathematical truth. More about finding meaning in an uncertain world (existentialism – absurdism) , see also my posts about Camus.

Sartre believed that human existence is the result of chance. We are responsible to build our own future, yet the future is uncertain and we cannot escape from the anxiety that is caused by uncertain events. Following the existentialists’ belief we are defined by exactly these choices and actions that are undetermined.

Existential uncertainty is a new kind of awareness, because it is the question that asks us how to live. In fact, it is a form of metacognition due to one’s own awareness of one’s lack of knowledge.

Heraclitus said that ‘change is the only constant in life’ and change always brings uncertainty. Stoics believe that we can control our opinions, desires and impulses and would recommend ‘change what you can, accept what you cannot’.

****** It is part of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) where patients work on their behaviour and thoughts and develop certain skills with a psychologist/professional. Feelings, thoughts and our behaviour are fully connected, intertwined and interdependent. To overcome difficulties, reach goals and/or deal with uncertainty the patient can minimise negative beliefs, stop following a certain automated train of thoughts, shift the focus to the brighter side etc. Often our thoughts are rather irrational and based on further feelings, anticipations or past experiences.

******* (genauer, in anderer Quelle: ‘Man muss den Dingen die eigene, stille ungestörte Entwicklung lassen, die tief von innen kommt und durch nichts gedrängt oder beschleunigt werden kann, alles ist austragen – und dann gebären… Reifen wie der Baum, der seine Säfte nicht drängt und getrost in den Stürmen des Frühlings steht, ohne Angst, dass dahinter kein Sommer kommen könnte. Er kommt doch! Aber er kommt nur zu den Geduldigen, die da sind, als ob die Ewigkeit vor ihnen läge, so sorglos, still und weit… Man muss Geduld haben. Mit dem Ungelösten im Herzen, und versuchen, die Fragen selber lieb zu haben, wie verschlossene Stuben, und wie Bücher, die in einer sehr fremden Sprache geschrieben sind. Es handelt sich darum, alles zu leben. Wenn man die Fragen lebt, lebt man vielleicht allmählich, ohne es zu merken, eines fremden Tages in die Antworten hinein.’)

******** The insurance of the patient asks an independent body (‘medizinischer Dienst’’) to evaluate the severity of impairment/need for support/skills left in different categories: mobility, communication/cognitive skills, behaviour/psychological issues, self-sufficiency, handling of illness-related tasks, everyday and social life; further: activities outside and household.

********* Germany spends about 1200 Euro/person more in health care which is quite a lot. Further differences are (aside of their funding): You have to wait ages for referrals in the UK, whereas in Germany you can basically see any doctor including specialists quite soon. During the pandemics, the German health care system proved to be more stable. There are more individual choices here in Germany. Lastly, Germany has a red two-tone sound ambulance, the yellow-green UK ambulance has an oscillating sirene.

1 thought on “From Uncertainty To (In) Therapy”